It’s midnight in southern Oregon, and my daughter’s little dog needs a last pee before bed, so I flick on the porch light and step out to find a 40-ish man in shorts and a T-shirt almost within reach, interrupted while tweaking his way towards the side of the house. If you don’t know what tweaking is, it’s the jerky, anxious, aggressive, twitchy, shitheady movements that tweakers make. If you don’t know what tweakers are, they’re the jerky, anxious, aggressive, twitchy, evasive, dishonest, light-fingered, impulsive, libidinally-haywire, semi-to-fully-psychotic shitheads tweaking around on methamphetamine. If you don’t know what methamphetamine is you gotta be Rip Van Winkle’s grandma, but, for the record, it’s the derangingly strong amphetamine derivative that the Wehrmacht was jacked to fuck on when blitzkrieging Europe.

“Kevin?” says the thing at my door, blinking and holding up a tweaky, cigarette-clutching claw as I point a 990,000-lumen flashlight at him. Intense light works wonders when repelling the creatures of meth, as do air horns and other sonic blasts. Oregon’s tweakers may not feel much pain, but they hate exposure. “Kevin?” repeats the shithead, before gibbering on with: “You don’t know him. I’m from Winston, Wilsonville, and up past Portland. Kevin said he’d be here.”

More from Spin:

- Julian Lennon and Gregory Darling Share ‘A New Dream’ They Have For Us All

- Frank Black: Catholic, Pixie, Teenager, Icon

- The 2025 Grammy Awards: Winners, Losers, Snubs, and Surprises

After giving the tweaker a minute to finish his looking-for-Kevin-schtick, I bark at him to get the fuck off my property, put the dog back inside (she’s a cuddler not a fighter), and return outside to ensure this trespasser does indeed fuck off.

“Well, fuck you Kevin,” he says, retreating downhill under stupendous illumination. The first night I tried the flashlight, a nearby resident thought a SWAT raid was in progress.

Lately I’ve confronted more than a few thieving wraiths and pilfering wastoids, including chancing upon one such degenerate a couple weeks back as he tried to force open a window at a nearby house. Another screeching twit who’s been terrorizing kids at a church-run, after-school activity center threw a punch at me. I’m sick to fuck of them. I’m done with the total selfishness, the idiotic self-indulgence, the slitherly hustles, of the perma-wasted. Luckily, I have a solid neighbor who — when the zombies tweak up our hill going into yards and looking in cars — pitches in to guide them to the exit. But he’s not on the scene tonight, so it’s a solo show.

Lacing up a pair of steel caps and grabbing Mace, I go for a slow drive. Since returning to Oregon after a near-lifetime in Australia, I have tightly embraced the American right of law-abiding citizens to strap up and equalize. But tonight I don’t need a gun to face the junkoids of Roseburg.

A block away, the tweaker is creeping through someone else’s yard. Time for a community announcement. “BURGLAR!” I roar loud enough to raise, and to deafen, the dead. “Get out of people’s yards you JUNKIE BURGLAR!” Darting clear of someone’s house with a bag in hand, he mutters, twitches, fizzes and comes at my car saying he’s going to kick my ass. But stops, perhaps unsure of who’s crazier. Oh, I can school you on that.

He backs up, mutters, moans, and now turns tail to run tweakily into the night.

Back home I view footage that my motion-sensor security cameras captured before the dog needed to pee. The ring of digital eyes first videoed him not only entering our yard but then seeming to get into the space under our front stairs. Tweakers, it should be noted, tend to build nests and hidey holes. It’s in their vermin nature. In the morning we find signs of disturbance beneath the steps: cigarette butts, displaced dirt, and mutilation of boards.

When I post a still of the man to a community group’s social media feed, someone sends a name, photos, and intel that this guy — who’s been under our stairs and creeping towards side entry points of my family’s home — is not only a voracious user of meth, but a violent rapist. Mind you, people say all kinds of things, yet when I run a background check I find the named man, who certainly looks to be the tweaky freak I shouted into the ether, is indeed up on charges of rape, assault, possession of controlled substances, and more (yet, in the wisdom of the law, he remains at large — praise be to our enlightened, humanitarian, progressive justice system).

The retrograde I recently interrupted mid-break in nearby also has quite a rap sheet, including a long string of burglary, theft, and drug offenses, including one highlight where he climbed through an old man’s bathroom window and attacked him. When I raised my voice, that shithead minced off, too, complaining that “You shouldn’t speak to me like that,” but of course I still see him tweaking about the neighborhood, scoping houses and yards.

On an evening that I take our pooch downtown to see late summer’s great swirling flocks of starlings, a tweaker crouches with a cigarette lighter and tries to set fire to the dog. “Don’t set fire to my dog,” I say, pulling the poor, petrified little terrier behind me.

“But the light. The light,” he says, doing sparkle hands. “It opens dimensions.”

“Don’t set fire to my dog. If you try again, I will stomp your head you fucking piece of filth. Understand?”

He stops doing sparkle hands, nods sideways, and scuttles away.

It’s been a long, long season for narco-fauna in Oregon, where their feed — meth and fentanyl — is plentiful and cheap. It’s often only a dollar a pill for “fetty,” while “clear,” as meth is nicknamed for the clarifying qualities that many wastoids claim they find in it — I shit you not — costs a few bucks for enough crystal to hear radios that don’t exist. This place is so awash in hyper-powered junk that the beaver could readily be replaced as the state animal by the tweaker. Putrid, grizzle-toothed — gnawing at everything and undermining or infesting homes.

And I’m down in the boondocks. Driving through Portlandia one evening I spot movement to the right and then a sidewalk tweaker flings a fire extinguisher into the traffic. I veer clear, but glancing back I see the SUV behind me stopped and stuck, cylinder jammed beneath, as the Pacific Northwestern junkoid who flung it dances in full tweak mode: shrieking gibberish, gesticulating, and lurching from side to side on his bow legs.

My best friend here has an inclination for meth. But he’s different. I can wholeheartedly say that Easton is a wonderful friend: when I landed in America, kid in tow, and life was at its hardest, he was kind and generous, and all with the easy grace of a good buddy — even though we’d just met. Easton’s a peerless listener and lively raconteur, both curious and worldly. He never pries or pities or plays therapist but instead says “Take my car,” suggests ping pong, or watching great boxing matches of yore, or following leads for a podcast we talk of making. It’s light and fun and it means everything.

Easton, now in his early 50s, was an athlete and political science scholar who lived and worked in LA, New York, Seattle, Portland, and other cultural hotspots, traveling abroad and living the high life. But after moving back to southern Oregon to care for his elderly parents, he detached from hustle and ambition. He wasn’t plugged into Important Scenes anymore. He didn’t earn much. And as his beloved father and then mother died, it seems he well and truly slid into a persistently limiting low — one which defused his spirit while infusing him with reasons why this is how it is now.

Not that I grasp this in the first year or two of our friendship.

For the longest time Easton doesn’t mention or give a glimpse of his meth use. When we hang out at the Kodiak Bar & Grill, loading the jukebox and thrashing it out at the ping pong table or going all cruise ship with shuffleboard, Easton can sit on a drink for a couple hours. He doesn’t duck out or repeatedly go to the bathroom or get tweaky. And he introduces me to great local characters like Hal, an older guy who was allegedly in a short-lived ’80s LA rock band with Hulk Hogan’s brother, has a pristine first-release Beatles album, and packs his own custom ping pong paddles. These evenings, every week or so, are a tonic.

But one time, when I’m bitching about another run-in with a tweaker, his particular smile prompts me to ask if he’s tried meth — which isn’t unusual here in this dirtbag arcadia. Plenty have, including partiers with a few years on them who partied through the illicit supply-side transition from the once widely-available speed — meaning coke’s poor cousin, amphetamines — to meth. While both substances can induce “severe behavioral effects,” as spelt out in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, the power of meth to do so dwarfs plain old speed (forms of which are prescribed as Ritalin and Adderall.)

Scientists attribute the Helter Skelter fury of methamphetamine to the sheer scale of dopamine-release it triggers in the brain. In moments of pleasure, our brains generate, and release, the molecule dopamine. Orgasm reportedly releases up to 200 units. Amphetamine about 250. Cocaine can clock 350. And meth? One thousand, two hundred and fifty. And the cyclone lasts for several hours.

Such a blitzkrieg hits the brain so hard and for so long that it causes cell death, and it’s so overwhelming that with heavy or sustained use comes psychosis — sounds and sights that aren’t there, bizarre and paranoid beliefs — which persist beyond the transitory pleasure and are accompanied by protracted insomnia, gut-wrenching anxiety, and a depressive plummet that follows the utter depletion of one’s capacity for pleasure.

And what is the escape route from the grisly, anhedonic funk? More meth. More cell death. More creeping madness. And then more depression.

“But I only have a little,” says Easton, “and only sometimes — like if I’m going to meet a lady.” I’m not sure if that means we should add sex’s 200 units of dopamine to crystal’s 1,250 or if that’s just washed away but, regardless, it sounds like Easton’s having a ball.

“I don’t have a problem,” he says.

We’re living in a simulation. At least it seems that way. The player gets bored with garden variety dysfunction so she (most SIMS players being female) installs a narco-mod, dialing down our stoicism while so spiking the potency of our vices that characters turn into gibbering tweaker rapists living under stairs, or shooting tranq and drooping at weird angles for hours, or smoking blue fentanyl pills and clearing sectors of the game via mass overdosing.

The player makes Oregon so awash in drugs it threatens to overwhelm the game. In 2020, she nudges a majority of Oregonian characters to vote YES to decriminalizing absolutely everything: meth, smack, fetty, flakka, blow, acid, angel dust, tranq, molly, jeeb, special k, vikes, kickers, and whatever the fuck other ups, downs, and sideways could previously get you tossed in the clink, fined heartily, and monitored.

The victory of ballot Measure 110 is a triumph for lobbyists of the Drug Policy Alliance, which spends a reported $5 million-plus championing the referendum with arguments such as: “Instead of arresting people for drugs, we should respect people’s bodily autonomy and offer support if they need it.” To keep things spicy for conservatives who love to hate meddling liberals, George Soros’ son, Alex, is on the DPA board of directors, while the philanthropic foundation of Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, reportedly tosses in another half million.

And from the stroke of midnight, February 1, 2021, “bodily autonomy” takes its throne: you can flaunt a “personal use” stash of your favorite poison and instead of whacking you with criminal penalties the most the five-oh can do is issue a $100 fine that will be waived if you call a treatment hotline, but get this: Oregon lawmakers ensure there is no penalty for neither paying the fine nor ringing some number. It’s all cool. Who wants to get fucked up!

Meanwhile, in order to meet, and to expand, demand for drugs, and to then enjoy the predictable consequences of all this respect for bodily autonomy, our player gapes the southern border and tasks the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación with flooding the West Coast with drogas muy baratos y muy fuertes. High times! And deadly times. Fatal overdoses in a state of about 4.2 million souls more than triple from 615 in 2019 to 1,862 last year. The death rate per capita likewise soars. Many may need help in Oregon, but only a tiny fraction seek it. Turns out that in Narcotopia getting clean isn’t a major priority. Au contraire, the new law and the accompanying abundance of product draw addicts to the state like liquid into a syringe.

Plus, just for an extra giggle, our SIMS player ramps up the weed thang to such absurd levels that she has Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan personally taking $10,000 per month plus bonuses from dope-slingers La Mota, who claim to operate the state’s finest “dispensaries.” After journalist-characters from the player’s Media Expansion Pack expose the payments, Fagan denies any impropriety but eventually resigns under pressure. Her boss, Oregon Governor Tina Kotek, is famously photographed at a Democratic Party Fundraiser partnering at pickleball with a founder of La Mota, the dispensaries of which are “currently carrying 50+ strains to choose from to suit all of your medicating needs.”

There’s a whole lotta medicating going on! Before the player redirects me here to SPIN, I spend a couple of years working for an Oregon company which requires job candidates to first pass a drug test with the expectation they’ll remain drug-free. But many colleagues are stoned: openly and always. One decides to apply for another job, which also requires first producing clean urine, so he gets a friend’s piss, tubes it, and smuggles it into the drug test via a concealed-carry belly-band holster. I forget to ask him if being stoned all the time is “recreational” or “medicinal.”

The player is entertained. Oregon’s a hoot!

Easton starts to look a little worn down, and his schedule changes in ways which make it harder to catch up with him. His hours of availability generally creep later than I, as a parent and working man, can match. Hal dies. Easton doesn’t go to the Kodiak much anymore, and when I do see him, there is often a different breed of folk around him. Dirtbags! These mighty archetypes of the Pacific Northwest breeze into his workplace at night, often logger-like in their lanky, chiseled machismo but with an icy, zappy, evasive air. If these guys join Easton and me for a round of darts they tilt their heads back, crack their necks, their knuckles, a joke, and then kerplunk, kerplunk, kerplunk. Then they’re out of the room, into another area of the building, somewhere else — or Easton is, telling me as he steps out to wait here, he’ll be back, and I keep throwing but the energy is gone. Most often I just head home now. Times have changed. When I was younger and had less duties maybe I would have stayed and, like Easton, been drawn to the shifty charisma of these tough guys with their cavalier, nocturnal adventurings.

Easton seems a sucker for their swagger and casually wild tales, and the more time — the more nights — he puts into hosting and hanging with them, the more disheveled he appears. One day he loans me a room to conduct an interview for something I’m writing. After three hours my subject leaves and after farewelling him, I sit back in a chair, spent from the mental workout. “Tired?” asks Easton.

“Yeah, talk about intense,” I say.

“Need some energy?”

“Huh?”

He smiles and pulls out a glass pipe, stained cloudy white.

“Ah, no thanks, mate,” I say, startled — troubled — that even his days are now crystalline. But he’s having a rough time. The business where he works is closing down with major uncertainty ahead. Meanwhile, one of his casual hook-ups is very dissatisfied with casual, he tells me, and has gone full psycho: full scorched earth. And Roseburg’s a small, blue-collar place where it can be hard for an underemployed political science graduate in his early 50s, with almost no assets and about to be unemployed, plumb out of confidence and with a banshee allegedly stalking and harassing him, to feel good in his skin.

Hence a boost.

The imaginary SIMS player loves it! She makes sure the crystal meth stays abundant, dirt cheap, and hyper powered, and she steers more chem-hungry dirtbags into Easton’s contracting orbit.

This region’s lean, wily, semi-nomadic hustlers are an interesting phenomenon — all summer and deep into fall they saunter about with a louche ease in hard-time jeans, shirts off in the sun to catch some rays on their washboard abs.

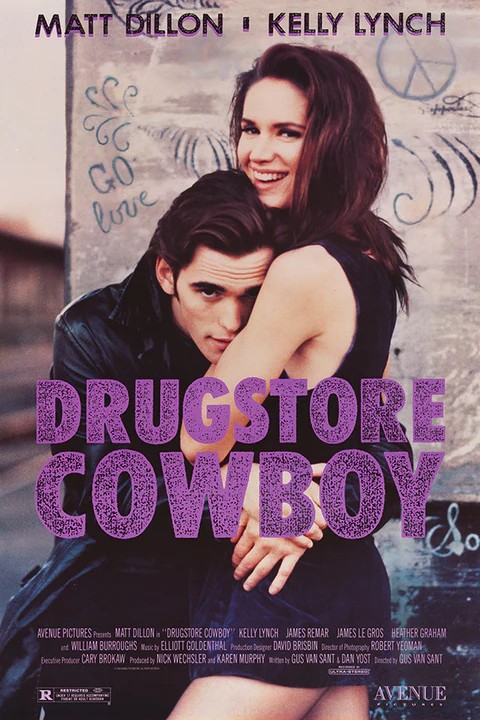

I suggest to Easton that we catch some classic Pacific Northwest-dirtbag cinema, figuring it’d be fun to compare what circulates around us with the charismatic crims and hustlers of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Drugstore Cowboy, and My Own Private Idaho.

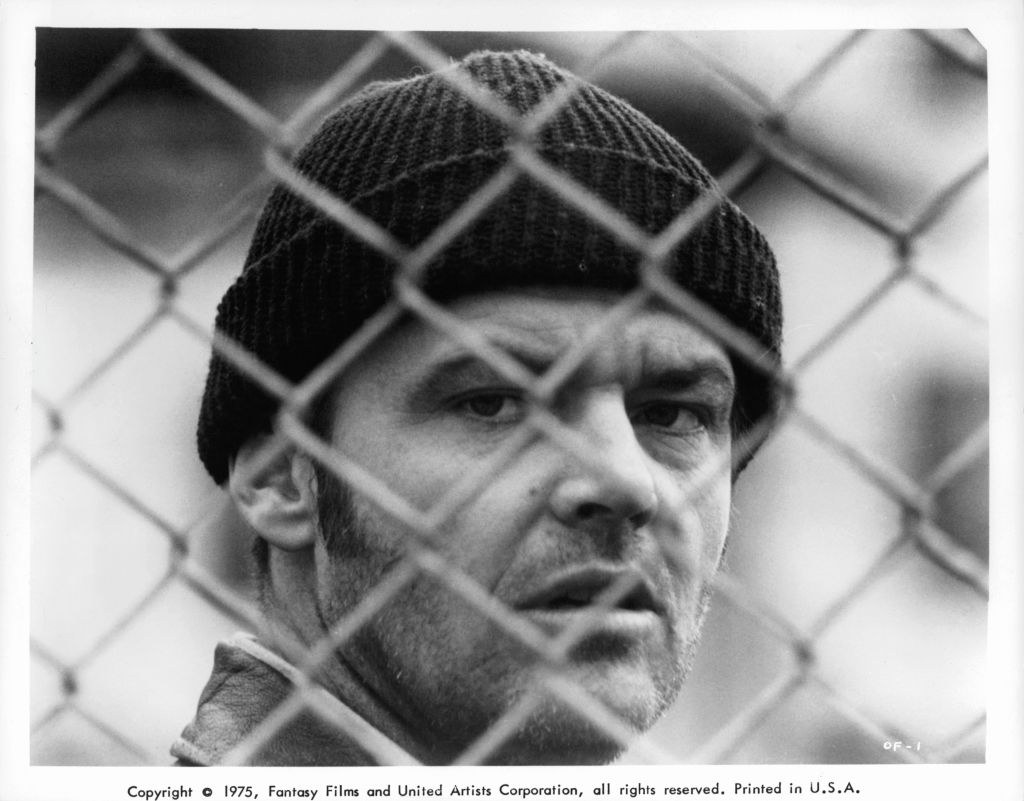

But Easton can’t meet early enough anymore to get a movie in before lame old me would have to split, so I just watch them in my own time. That seamy swagger of Jack Nicholson as über-dirtbag Randle McMurphy in Cuckoo’s Nest could have been shot here yesterday. Matt Dillon as Bob Hughes, lead junkie bandit of Drugstore Cowboy would also slot right in now, as would the late River Phoenix as conflicted hustler Mike Waters in Idaho.

These Oregon movies are decades old, and draw from source material even older. But they can sure feel like a night at Easton’s in 2024. And maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t think my dear friend is tough enough to hang out with this breed. In the end, dirtbags themselves aren’t even tough enough for it, judging by my sightings of such creatures in their late stages — so many aging junkies, tweakers, boozers, and battle-scarred casualties still work as best they can the easy-come-easy-go macho-hobo schtick, but 10 years ago would Mr. Fuck-You-Kevin be so readily chased around town by an angry dad with a little dog?

And many aren’t even present as burn-outs. They’re dead.

But closer to their prime, as some of those spinning around Easton seem to be, they can have a certain spark. So, curious about these iconic ne’er do wells of the Pacific Northwest, whom the player is dialing into the game now bigtime, I get in touch with Gus Van Sant, former longtime Oregonian and director of both My Own Private Idaho and Drugstore Cowboy, both largely set in Portland.

“It strikes me that I’m seeing the people of your movies, and the Randle McMurphy of Cuckoo’s Nest, these charismatic dirt bags from hell, everywhere here in Oregon,” I say to Van Sant. “The swagger, the being in and out of trouble with the law, the pushing it with drugs, the mischievousness, a kind of dangerous immature sexiness. Switch the clothes and they could even be out of the Depression era, right?”

“They’ve always existed there,” says Van Sant. “Since the mid-1800s, anyway. A lot of it comes out of the shipping industry, the logging, the fishing industry. It’s Jack London. Neil Cassady [Jack Kerouac’s macho muse] was one of them. The seasons would come and go, like salmon season would come, and then people would move into the hotels in Portland’s Old Town, then they would move somewhere else to work. Maybe Alaska, and then Washington and Oregon. It’s kind of the mountain man thing. They’re still the same people.”

“The wild man hustlers and charismatic dopefiends around now are people like Matt Dillon’s character, right? These archetypes like out of London and Kerouac, but in a world of modern drugs.”

“Yeah,” says Van Sant. “The people in Drugstore Cowboy were those types of people. And all of the ones in the story were actually in prison. James Fogle, who’d written the [autobiographical] manuscript, was in Washington State Penitentiary [at Walla Walla]. The lead character that Matt Dillon played was in a different prison.”

I raise as a successful variant of the chemically altered Pacific Northwestern hustler the young Steve Jobs, who in the early 1970s famously dropped out of Portland’s Reed College but stayed on campus anyway, dropping acid, “auditing” classes from Shakespeare to modern dance and calligraphy, collecting discarded bottles to cash in, and hitchhiking for free meals.

Van Sant knows this history well, pointing out that Jobs attributed the aesthetic revolution of early Apple computers to soaking up calligraphy as a dropout hanging around Reed. No longer need our screens look like death-by-IBM.

After breaking through with Apple, Jobs gave a speech at Reed, noting that the Portlandian liberal arts institution nurtures the “spirit of adversity,” and tipping his hat to the college for it, saying: “I want to thank you for teaching me how to be hungry and how to keep that with me my whole life.”

But the game has changed — that era’s drugs eclipsed by the obliterants flooding in now. Even heroin, as Portland’s Dandy Warhols sang in 1997’s “Not If You Were the Last Junkie on Earth”, is so passé. We are now in a synthetic era in which poppy fields, like coca plantations, are not needed. More natural “legacy” boosts — often also meaning more natural dependency and terminal ruin — are relics: softcore nostalgic shit long overrun by stamped pills of fentanyl (or now the even stronger nitazenes) along with sheets and shards of crystal motherfucking methamphetamine. But this tweak of the simulation comes after Gus eases off getting his high times in Portland. “In the ’90s I was closer to the drug culture,” he says.

I head north on Interstate 5 to see the terminus of this culture, these games, those throughlines of Oregon’s and America’s narcotic transcendentalism. In Portland’s squalid Chinatown I meet local photographer Tara Faul, who has spent the past few years documenting mass addiction and death. Along with a camera, she carries a toy trash can filled with naloxone dispensers and routinely toots up the noses of the overdosed, but it’s not always in time and she has seen scores die.

And it’s worth contemplating that while more than 1,800 people are estimated to have died of drug overdoses in Oregon in 2023, the national total that year was more than 100,000 dead. Looking back 10 years, figures from the National Center for Health Statistics show us closing in on 900,000 corpses, with millions of relatives and loved ones left wracked by grief, regret, sorrow, and anger.

Our player is having a ball!

Tara and I find an emaciated, bearded, curly-locked young man with wandering narco-sage vibes sitting on a low garden wall, four blue pills grouped beside his hand. Robert, as he calls himself (although the hospital band on his wrist begs to differ), talks rapidfire of his druggy travails across America, of dumpster diving at Aldi supermarkets in Pennsylvania, or was it Missouri, of methy times with neo-Nazis in southern California going sour, and of assorted quasi-intellectual gibberish, the quality of which he sometimes critiques. Off-color bubbles and droplets of drool spool and fall from his mouth as he speaks. And when he doesn’t. His hand covers the fentanyl pills and then doesn’t. He nudges them, and then leaves them.

“They can go for a dollar,” says Robert, “but I gave eight bucks, so these were two dollars apiece.” His face is a death mask: gaunt and soiled, teeth pebbly, eyes dilated but piercing in their last hint of blued luminescence. I think of hunger strikers — of Bobby Sands and the IRA — rather than those whose starvation is unchosen, but Robert’s cause is not political, nor national, neither anti-imperial nor quixotic, but instead the fall as gravitational cause: aka, the unforgiving and accelerating confluence of psychological vulnerability and pharmaceutical hyperpower. “They were going to be two dollars and some change apiece, but I got one extra,” he says, his eyes tracking sideways as he works it through. “They range from a dollar to four dollars. When I first found these in San Diego they were asking ten dollars apiece and I’ve seen people ask that up here before, but they’re not likely to get it from many people unless they’re very desperate or unless they can make a claim that they’re extra very good.”

Asked what meth costs in Portland, Robert says, “It’s free in this world because it doesn’t help anybody. That’s something I say. It is anywhere from that to a little bit too expensive than you would like, but never expensive really. You can throw a dollar at somebody and get some meth.”

“You can just get a dollar’s worth?” I ask.

“You can get a dollar of meth and that’ll be a shot,” he says. “Sometimes somebody will throw it at you. What it really costs is, ‘Do you have any meth, please?’ And somebody will smoke with you if you can’t pay for it.”

Asked how long his four fentanyl pills will last, Robert maneuvers them around on the stonework. “We shall see,” he says. “I could smoke them all at a drop. I’m being very good right now. I’ve had these for more than 30 minutes and have not broken into one — because I don’t have any foil.”

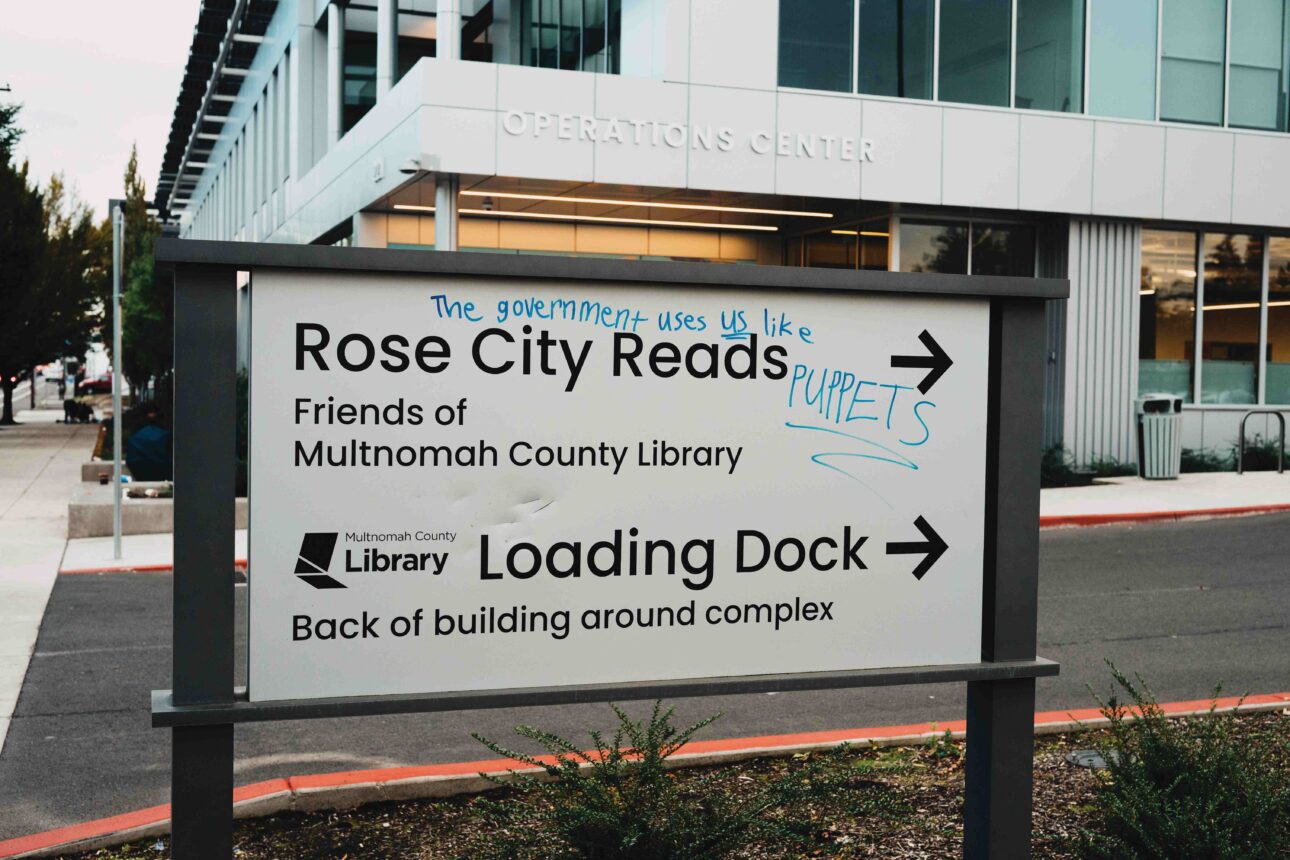

Downtown Portland is in Multnomah County, the health department of which last year decided to hand out free aluminum foil and straws for smoking fentanyl, as well as free glass pipes for smoking meth. Part of its “harm reduction” ethos, the free drug paraphernalia program was halted after those pesky journalists wrote about it, sparking a public backlash.

So Robert here, who tells me he is 29 and looks to be shimmering between this world and deletion, hasn’t been able to fetty up as fast as he would have otherwise.

Another consequence of vote-threatening public discontent with mass chemical slavery and the abject squalor, the thieving, the degeneracy, and the organized crime that comes with it, has been the recriminalization of drugs in Oregon this September. It’s only at misdemeanor level, and even that can be avoided if the arrestee agrees to be “deflected” to possible treatment in the future. Nevertheless, Soros and Co.’s Drug Policy Alliance mouths off about even this like a defeated lawyer in her cups, saying that the slight rollback followed “an intense disinformation campaign.”

Yeah? Really? Many zonked assholes hurled fire extinguishers at your cars, dickheads?

So Robert here, sitting in broad daylight smack bang in downtown Portland with four fentanyl pills on open display beside him, is now being slightly legally naughtier than during decriminalization.

But there are no cops around. Just legions of junkies like Robert and a few security guards that I don’t see do anything.

“After you smoke these,” I ask, “how long will it take you to get dopesick — to start withdrawing?”

“Pretty quick,” says Robert, still rearranging his pills. “In 10 hours I’ll be sneezing and I’ll be breathing poorly, and I’ll be maybe fetal for a while. But if I get frustrated in a motivational way I’ll get up and I’ll find it. If I sink into it [withdrawal] then I’ll sink into it and I’ll take some time to get up and get well again.”

If the blue pills kill Robert, or, to put it another way, if Robert elects again to exercise his bodily autonomy by self administering an extremely dangerous analgesic and dies, then our player will have another micro-tragedy in her macro-death mod to feel godlike about as she twiddles the game settings and watches how it plays out.

“Nobody should be an addict,” Robert says, slow and raspy. “Unless they are reasonably sure that subcultural context demands that the decision be made. Or in the case of it it makes you feel good. That’s all. I mean, what’s addiction? What’s addiction? What’s irreplaceable in your life? But nobody lives entirely without the extraneous. And nobody lives entirely without the contra-indicable.” Robert wheezes and his eyes flutter like he might keel over. “And nobody’s got a claim to ‘That stands outside of what is a healthy thing to pursue with tenacity.’” His eyes open. “But drug use is really a non-issue for me because anybody can do pretty much fucking anything they want — if theyr’e in the bounds of the bounds of the bounds.”

As I say farewell, Robert tells me that to accurately describe addiction, “a person would have to be simultaneously sober and high.” He says this is a difficult state to achieve, “because I don’t want to be in my feet. No, I don’t.”

Sober and high is perhaps a description of the player, hooked as she is on the game, but detached as she is, and willing, as she has proven in countless previous great cycles of the simulation, not only to kill countless characters but to terminate entire scenarios and all of us with them, and then spawn a new evolution from zero. Or who knows — maybe she’s long been A.F.K. (aka Away From Keyboard).

But why do we play into it? Why are we so averse to pain?

Tara and I drive northeast to 122nd and Glisan, pulling into a McDonald’s where the drive-thru needs to be negotiated slowly. Wouldn’t want to bump one of the droopers or any of the narco-loco elements glitching out with fastidiously repetitive fiddles of their bundles of bundles of bundles of detritus. “Dealer,” says Tara, nodding towards a man smooth-cruising 122nd’s sidewalk on a push bike, slowing as he passes clusters and sprawls of chemical consumers.

We find a guy with one leg laying on the ground complaining as an able-bodied gentleman strides past pushing a wheelchair. “That’s mine,” says the amputee. Tara and a fentanyl-addicted woman who’d been sitting with him catch up with the alleged thief, who says he needs the chair to move some pallets but promises to bring an even better one back tomorrow. He’s apparently had this man’s for weeks, rolling it up, down, and all around these parts as the amputee watches and grizzles in frustration.

“How are you getting around?” Tara asks the one-legged man.

“Hopping.”

A woman gripping her bundle thrashes on her side like a fractured breakdancer, limbs jerking with each guttural moan and howl. “That’s not ours,” said a man sailing by. “We only sell good drugs. That’s bad drugs.”

Easton has taken to wearing a wig at night, as he in all earnestness tells an assembled group of his non-dirtbag friends over dinner and a drink he never finishes. “It’s for walking home,” he says, pulling a cheap shaggy party wig out of a sports bag. This revelation comes after an evasive, defeated-feeling, and less than coherent account of how the dirtbags circling him have robbed him of his savings as well as the old car he’d loaned me when I was in such need, and why the police might now be surveilling him when he walks home at night. Hence the wig.

He looks gray and clammy.

I am stricken.

“Hi can you call me,” messages his girlfriend two weeks later.

He was found dead this morning. Age 52.

Three days later I part a curtain at a Roseburg funeral parlor and walk to the corpse of this man I love. The morticians haven’t made him up but just brushed his hair and drawn a blanket to his throat. His color is better than it has been, if a little ruddy, and his smile is again so wonderfully warm.

But when I put my hand to his face, he is cold and gone.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.