When filmmaker Bernard MacMahon began thinking about making a documentary about the early days of Led Zeppelin, he was warned against it. The British director recalls, “We had a couple of people saying to us, ‘The band will never, ever agree to do this, and you’re mad.’”

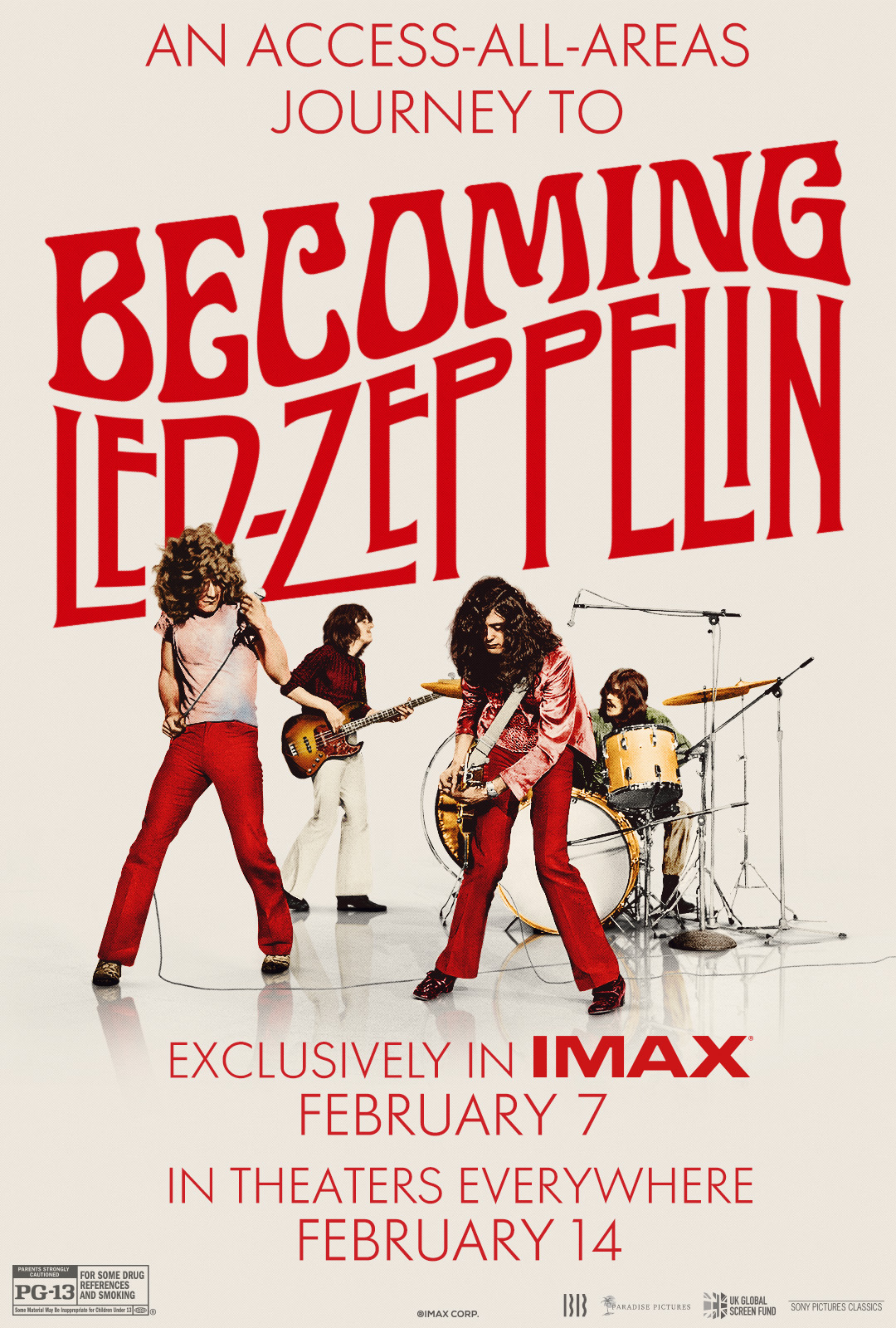

MacMahon and his producer and writing partner Allison McGourty were not deterred at all, and spent seven months meticulously preparing their pitch to the hugely influential hard rock band and original monsters of rock. That gamble has paid off in the form of the newly-released Becoming Led Zeppelin, the first documentary to have the participation of surviving band members Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, and John Paul Jones (drummer John Bonham died in 1980). In just a week’s time, the film was greeted with raves and became IMAX’s biggest-grossing music film of all time. It is now going into wide release in over a thousand theaters spread across every state in America.

More from Spin:

- Horsegirl’s Sophomore Album is a Beautiful and Chaotic Coming-of-Age Story

- The Wombats Frontman Matthew Murphy Charts a New Course

- D’Angelo Returning To Live Action At Roots Picnic

It is the first project from MacMahon and McGourty since American Epic, a monumental history of early recorded music in America that laid the foundations for what we still know today as the roots of blues, country, folk, and more. The four-part documentary series for PBS and the BBC was widely acclaimed and hit a bullseye in the particular musical obsessions of three British musicians: Page, Plant, and Jones.

Like American Epic, the new documentary was deeply researched and took years to complete. An early cut of the film was shown as a work-in-progress at the 78th Venice Film Festival in 2021. Becoming Led Zeppelin explores the personal histories of each band member, leading to their first meeting, earliest gigs, and first two albums (both released in 1969) whose songs were mysterious and explosive, mingling deep blues and British folk.

Before the band, guitarist Page and bassist Jones were hot session players in London, hired to liven up pop songs of the moment, anyone from the Kinks, the Who, and the Rolling Stones to early David Bowie (then named David Jones). Bassist Jones even played on the James Bond theme song “Goldfinger.” From 1966-1968 Page was a member of the Yardbirds.

Meanwhile, in the West Midlands of England, Plant and Bonham were toiling in far less glamorous clubs, working toward their musical goals in a series of short-lived bands. MacMahon calls the unlikely meeting of these four players a miraculous event that illustrates the power of collaboration: “Particularly with people that appear like they have very little in common with you, the whole can be a lot greater than the sum of the parts.”

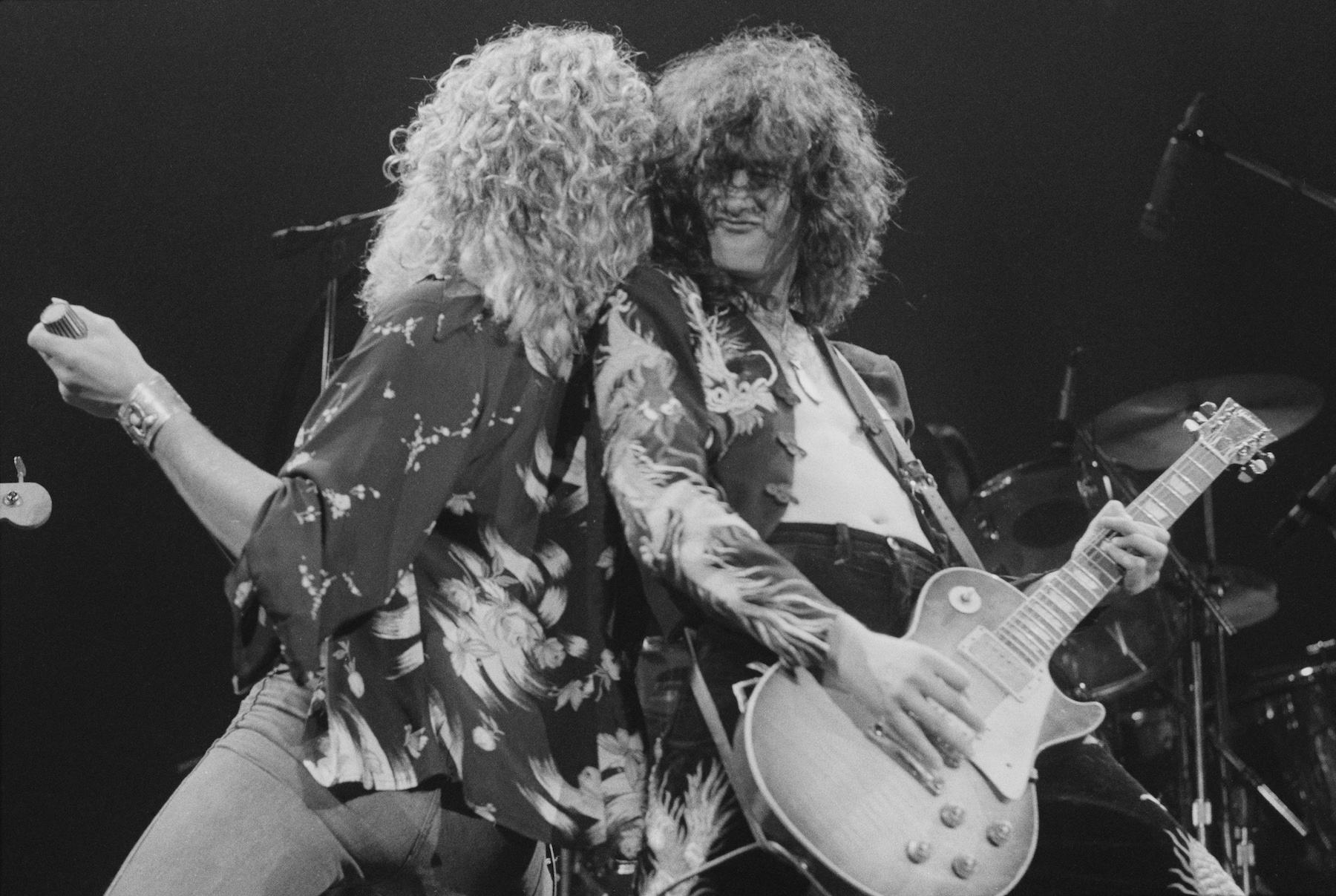

The new band was already a fully realized force that first year, which is captured in vivid black-and-white TV footage of a performance in Gladsaxe, Denmark. The band was only months removed from their first meeting, and the foundational elements of Led Zeppelin are already present in four now-classic songs performed that day: “Communication Breakdown,” “Dazed and Confused,” “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” and “How Many More Times.”

Those tracks would appear on Led Zeppelin’s 1969 self-titled debut album, with cover art depicting the doomed Hindenburg dirigible in mid-explosion. Many critics were unimpressed, and U.K. bluesman John Mayall dismissed Zep as a “parody of the blues.” According to rock folklore, Who drummer Keith Moon said the band’s music would go over like a “lead balloon.”

History has long since proved those naysayers wrong, and the film takes fans back to that moment of birth.

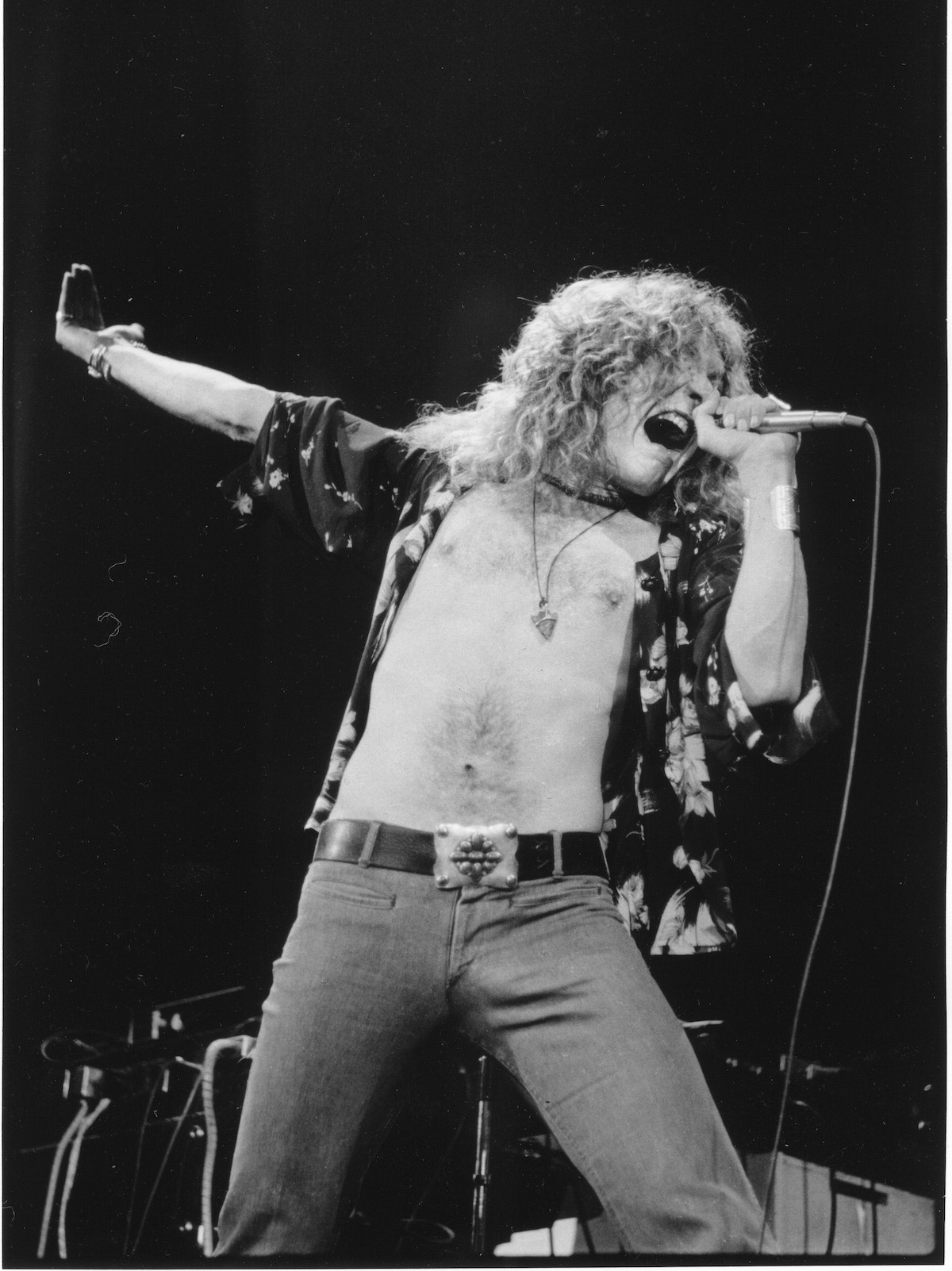

As much as some early reviews stung, band members were also experiencing intense fan reaction on their first U.S. tour, which was so extreme that the players didn’t dare talk about it when they returned home to the U.K. The album was still months away from release at home.

By the time MacMahon and McGourty first met with Page, the filmmakers prepared a detailed storyboard for the film. The guitarist was in good spirits, but would occasionally toss out a trick question to test their depth of knowledge. One question Page asked was: In what band did Page first see Plant sing? The answer was obscure but came easily to MacMahon: Obs-Tweedle. Page replied, “Very good. Carry on.”

The meeting lasted seven hours, a good sign. But the filmmakers still had two other band members to convince.

Jones had just watched American Epic for the first time before meeting with them, and was quickly won over by its section on country music originators the Carter Family, which included new footage shot in isolated Maces Spring, Virginia. Jones made the same pilgrimage on his own, and met some of the same people there.

“He must have felt looking at it that it captured where he’d been, but we were also a kindred spirit,” says MacMahon. “We both made the same pilgrimage and considered that important enough. You have to trek to get there. That’s not an easy journey.”

For Plant, the filmmakers began a different kind of journey, first meeting with him backstage at a show in Perth, Scotland. The singer then invited them to his show in Sheffield, England, and then to another in Los Angeles. Plant was putting them through a cheerful endurance test, but the filmmakers were used to the hunt.

“We traveled across 38 states making American Epic,” notes McGourty. “We’ve been to literally the middle of nowhere. We’ve been in fields in deep Mississippi. And one of the few people that’s been to those places is Robert Plant. He’s always turning up in weird places.”

They were backstage with Plant amid 200 other guests at the Orpheum Theatre in L.A. “He walks over, and comes up to us and says, ‘OK, so we are going to do this?” Without quite answering his own question, Plant asked the couple to follow him again, this time to Birmingham. When they arrived, they found Plant this time with Pat Bonham, the drummer’s widow.

“He’s obviously talked to her and said, ‘I think this is a good idea,’” recalls MacMahon. “He was committed to do it.”

Talking now over Zoom beside McGourty, the director holds up his cell phone to show a snapshot from their first meeting with Page, the mysterious guitar hero all smiles. And McGourty raises hers to show their meeting with Plant and Mrs. Bonham.

For a band that had never before agreed to participate in a documentary, and generally turn down most interview requests, their work with the filmmakers went rather smoothly. Most surprisingly, the Zeppelin members agreed to give MacMahon and McGourty full creative control of the film.

“Once they decided to do it, they were all in,” says McGourty. “There wasn’t any point at which they tried to tell us not to do something. It was the opposite. They brought things. They said, ‘Well, do you know about this photograph?’ They came with bags of things.”

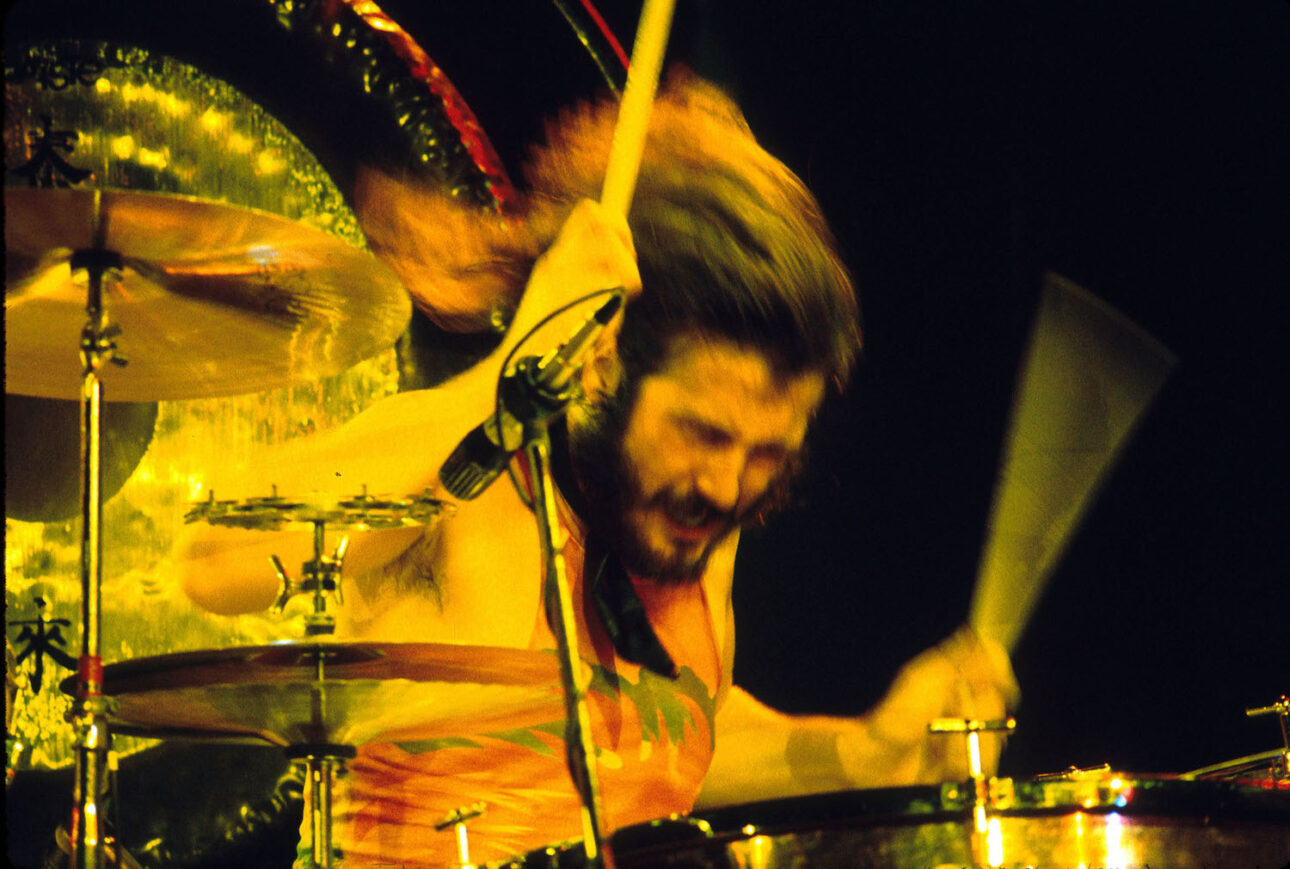

Rather than a traditional parade of talking heads, the Zeppelin story is told from the band members’ point of view – even including their late drummer, gone since a tragic day of heavy drinking in 1980. Plant did wonder if that could really be accomplished, since Bonham gave few interviews during his life. “How are you going to do that?” asked Plant. “I’ve never heard anything with him saying more than a couple of sentences.”

Bonham’s voice is included largely from a recorded interview found unlabeled at an Australian radio station. In that and other interviews unearthed during their research, Bonham’s recollections and lingering excitement about the early Zeppelin days is captured in the moment, while the surviving members are older and more reflective as they look back.

At the U.S. premiere at the Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles in January, the filmmakers were approached by Jager Bonham, grandson of the Zeppelin drummer, who said, “I want to thank you for making this film. It’s the first time I’ve heard my grandfather’s voice.”

The documentary ends with a thundering 1970 performance of “What Is and What Should Never Be” at the Royal Albert Hall in London, and it makes for a triumphant finish of this chapter of the Zeppelin story.

But there is an earlier milestone that takes the band’s journey into the cosmic and consequential: On July 21, 1969, Led Zeppelin played The Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park, the same date that Apollo 11 astronauts landed on the moon. The documentary has footage of the band onstage that night, shot from outside the performance tent, and the camera swings up toward a crescent moon in the night sky.

Carrying that connection even further, the American astronauts returned to earth on the same day that Zeppelin received their first gold record award. In the film, Plant recounts that day of personal triumph while keeping his band’s award in perspective with the historic events that had most of the world’s attention.

MacMahon says, “In this very unselfconscious way, he is going, ‘We were just this little thing. And nobody noticed that we got a gold disc that day, but it mattered to us, you know?’”

In a bit of subliminal foreshadowing of other ‘70s rock revolutions to come, the end credits are accompanied by Zeppelin covers of two Eddie Cochran tunes: “Something Else” and “C’mon Everybody.” To British audiences especially, those old ‘50s rock songs are closely associated with the Sex Pistols, who transformed them into eruptions of bristling punk rock later in the 1970s. The Zep versions are presented as a challenge.

“I had some punks watching the film in London, and when that happened at the end, they went, ‘I know why you put those there. Fucking hell, they’re ferocious!’” says MacMahon with a grin. “What Zeppelin is showing you in January 1970 – a full six years before the Sex Pistols – is they are every bit, if not more, punk and ferocious in their coverage of those songs than the Pistols would be.”

Regardless of your particular tastes in Cochran covers, MacMahon hopes a deeper message comes through the film about dedication and perseverance. Paraphrasing Page’s last line in the doc, the director says, “If you have something in yourself that you think is different, you’ve got to work and work and work at it. But if your aim is true, you will achieve your dreams.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.