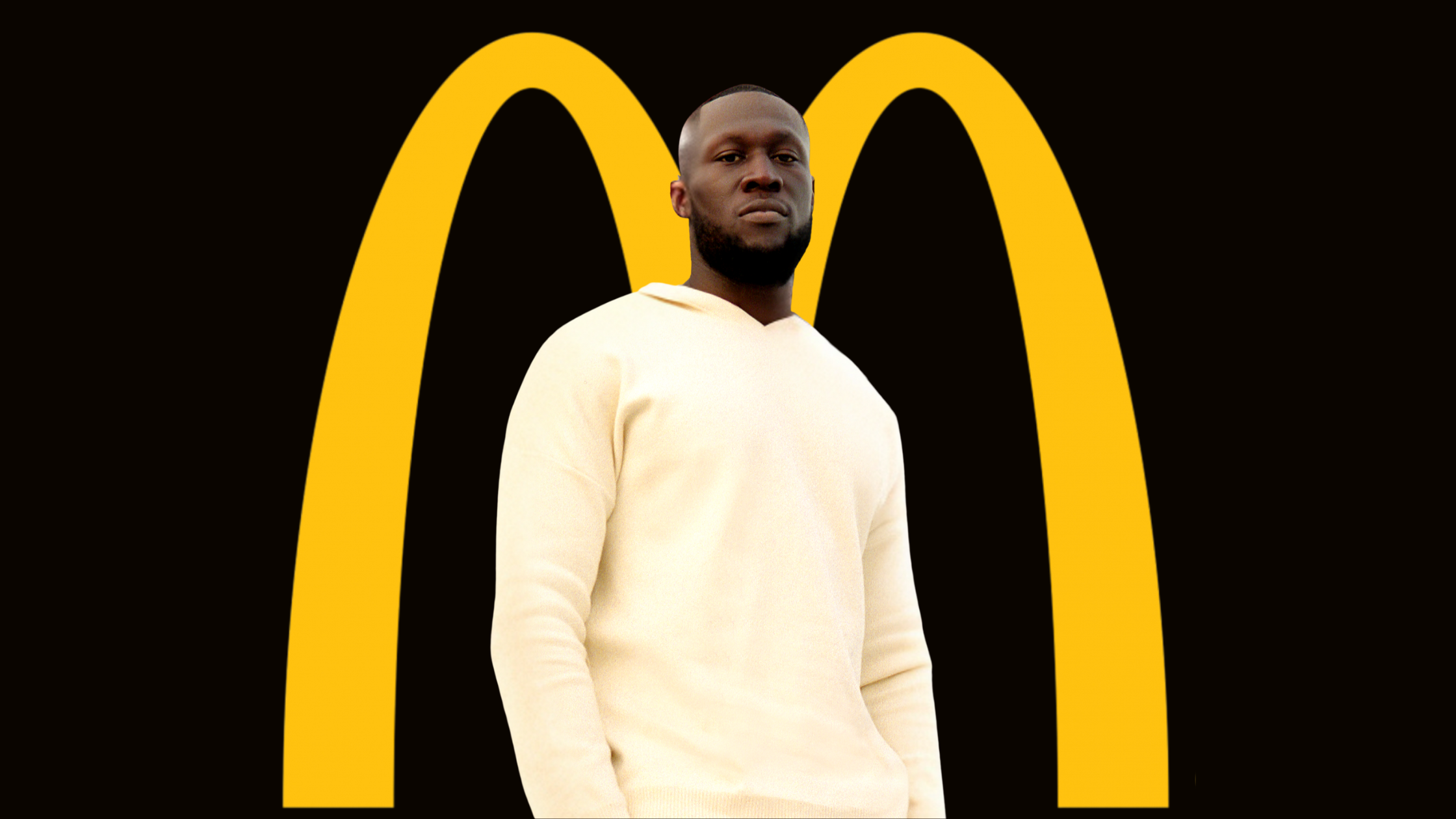

Stormzy has responded to backlash over his partnership with fast food brand McDonald’s and in particular to claims that his deal with the brand led to him removing an old Instagram post in support of Palestine.

Those claims grabbed attention because the rapper’s tie up with McDonald’s was criticised in connection with the fast food chain’s activities in Israel. In a statement issued on Friday, Stormzy insists that the brands he works with “can’t tell me what to do and don’t tell me what to do otherwise I wouldn’t work with them”.

As for the archived Instagram post, he continues, “I didn’t archive the post where I came out in support of Palestine for any reason outside of me archiving loads of IG posts last year. In that post, I spoke about #FreePalestine, oppression and injustice and my stance on this has not changed”.

The backlash to the McDonald’s deal, and Stormzy feeling the need to respond to it, is a reminder that there is now a political dimension to brand partnerships in music which artists – as well as festivals and other music organisations – need to consider.

That consideration might result in brand deals being abandoned altogether, but at the very least all parties involved in a partnership probably need to have a communications strategy in place if any kind of political backlash is likely.

In recent years festivals in particular have run into issues when they ally with sponsors that have connections to either environmental concerns or military conflicts, in particular the conflict in Gaza. That has often resulted in people booked to perform or appear at those events being pressured on social media to pull out.

In the case of Stormzy’s partnership with McDonald’s, many critics have honed in on the October 2023 controversy around the fast food brand’s franchisee in Israel giving free meals to Israeli military personnel fighting in Gaza. Given that controversy, some have argued, the McDonald’s deal seems inappropriate for an artist like Stormzy who has previously spoken out in support of Palestine.

Although at the time of the controversy, in 2023, McDonald’s itself insisted that it was not “funding or supporting any governments involved in this conflict”, the actions of its Israeli franchisee nevertheless resulted in a global boycott.

The Guardian also notes that “while the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment And Sanctions movement does not name McDonald’s as one of its central targets for consumer boycott, it continues to support the broader ‘organic boycott’ movement against the company”.

In the past a key consideration for artists entering into brand deals was whether doing so would be seen as a “sell out” damaging their artistic credibility. But today a possible political backlash is a bigger concern.

Discussing how he approaches brand partnerships, Stormzy’s statement continues, “I do my own research on all brands I work with, gather my own information, form my own opinion and come to my own conclusion before doing business”.

Explaining why he decided to issue the statement about the backlash to the McDonald’s deal, he goes on, “I’m writing this because I know there are people out there who have supported me and rooted for me who are genuinely confused and hurt by what they think has happened and I want to give those people clarity so I hope this helps”.

“I understand it must feel disappointing and disheartening when it seems like someone you’ve championed has compromised their beliefs for commercial gain”, he says, before adding, “this isn’t the case here”.

Some of the boycott campaigns over festival sponsorships have been successful in that the festivals have ended their deals with targeted organisations. Live Nation ended its deal with Barclays, SXSW with the US military and the Edinburgh International Book Festival with Ballie Gifford, which had investments in fossil fuel companies.

However, some have criticised online campaigns that pressure artists, especially independent and early career artists, to join festival boycotts. And, of course, the companies pushed out of music and culture sponsorships generally don’t actually change their policies or operations, instead simply spending their marketing budgets elsewhere, often in sport.

Which isn’t in itself a reason not to take a stand against artists or festivals working with brands that some, or many, in the music community believe shouldn’t be endorsed. But it is definitely worth considering when assessing the efficacy of different campaign strategies.