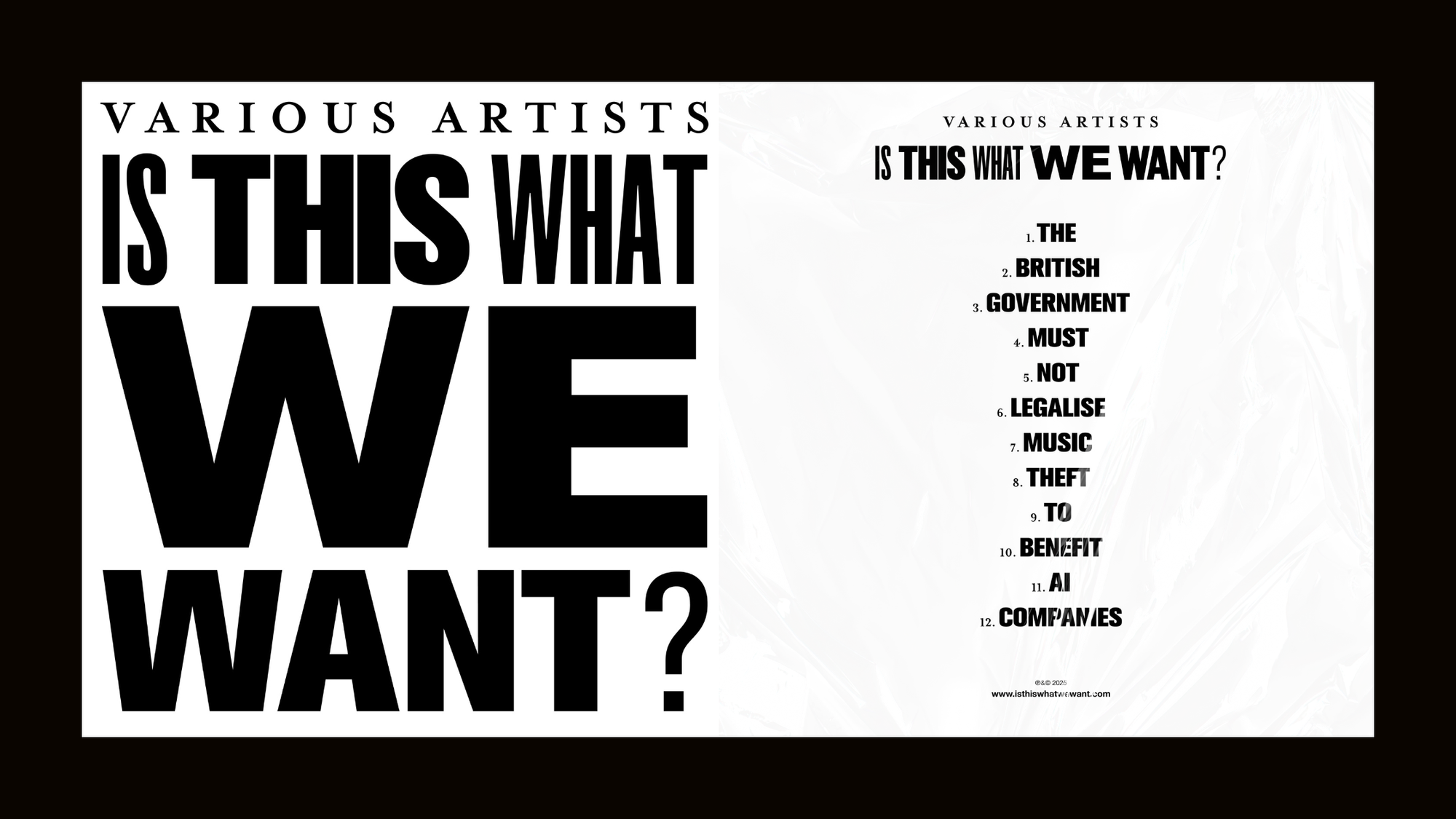

More than a thousand musicians have collaborated on a new silent album called ‘Is This What We Want?’, released to protest the UK government’s plan to introduce a new copyright exception for the benefit of AI companies.

The release coincides with the deadline for the government’s big consultation on copyright and AI, which leads with the proposed new exception. That deadline has also prompted many UK newspapers to run adverts today declaring that “the government is siding with big tech over British creativity”.

The silent album features recordings of empty studios and performance spaces, and has brought together the likes of Kate Bush, Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, Billy Ocean, Ed O’Brien, Jamiroquai, Imogen Heap, Riz Ahmed, Tori Amos, Hans Zimmer and Max Richter.

It has been coordinated by Ed Newton-Rex, the musician and AI entrepreneur who quit his job leading music projects at Stability AI over its position that AI companies shouldn’t have to get permission to use copyright protected works when training generative AI models. Newton-Rex founded his first music AI company, Jukedeck, in 2012, which was then acquired by TikTok owner ByteDance in 2019.

The government’s proposal to introduce a new text and data mining exception into UK copyright law would allow AI companies to access existing copyright protected works without getting copyright owner permission.

Although unlike previous proposals for such an exception, this time copyright owners would be able to ‘opt-out’ by reserving their rights through a yet to be determined process. Whenever the opt-out was exercised, AI companies would still need to get copyright owner permission.

Nevertheless, even with the opt-out, this exception, says Newton-Rex, would still “hand the life’s work of the country’s musicians to AI companies, for free, letting those companies exploit musicians’ work to outcompete them”.

Ministers are very keen for the UK to become a leading player in AI and are constantly told by the tech sector that, for that to happen, British copyright law needs to be more flexible.

Newton-Rex disagrees. Not only would the proposed copyright exception be “disastrous for musicians”, but – he says – it’s “totally unnecessary” because “the UK can be leaders in AI without throwing our world-leading creative industries under the bus”.

Max Richter, who recently spoke in Parliament about the proposed new copyright exception, is among the musicians quoted alongside the release of ‘Is This What We Want?’.

He states “the government’s proposals would impoverish creators, favouring those automating creativity over the people who compose our music, write our literature, paint our art”. Meanwhile Kate Bush asks the simple question, “In the music of the future, will our voices go unheard?”

The last Conservative government also proposed introducing a new text and data mining copyright exception. That plan was abandoned after a backlash from the creative industries, including the music industry.

The current Labour government hoped to placate the creative industries by adding the opt-out. It’s also keen to stress that there is already a text and data mining exception with opt-out within the European Union, so the government’s proposals basically bring the UK in line with the EU.

However, the creative industries argue that the opt-out system doesn’t really work. And even if it did for big rightsholders like major record labels and film studios, inevitably many independent creators wouldn’t know how to reserve their rights, putting them at a disadvantage. Hence the creative industries continued opposition to the proposed new exception. Indeed, that opposition this time round is much more visible.

Pretty much all the creative and copyright industries are aligned on this, including the newspaper sector, which is why so many newspapers in the UK are now running an ad campaign that seeks to rally public support for the campaign against the new exception.

Owen Meredith, CEO of the News Media Association, says, “We already have gold-standard copyright laws in the UK. They have underpinned growth and job creation in the creative economy across the UK – supporting some of the world’s greatest creators – artists, authors, journalists, scriptwriters, singers and songwriters to name but a few. And for a healthy democratic society, copyright is fundamental to publishers’ ability to invest in trusted quality journalism”.

When launching its AI consultation, the government noted that “AI firms have raised concerns that the lack of clarity over how they can legally access training data creates legal risks”.

But the copyright industries do not agree that current copyright laws are unclear. Meredith continues, “The only thing which needs affirming is that these laws also apply to AI, and transparency requirements should be introduced to allow creators to understand when their content is being used”.

“Instead”, he goes on, “the government proposes to weaken the law and essentially make it legal to steal content. There will be no AI innovation without the high-quality content that is the essential fuel for AI models. We’re appealing to the great British public to get behind our ‘Make it Fair’ campaign”.

Of course, the tech sector has been in full on lobbying mode in recent weeks too, as it tries to get the copyright reforms it says it needs.

Tech companies are mainly piling the pressure on Kyle and the Department For Science, Innovation & Technology, while the creative industries see the Department For Culture, Media & Sport – and culture secretary Lisa Nandy – as their allies. Which means the policy the government ultimately adopts may well depend on the outcome of a ministerial stand-off between Nandy and Kyle.

Although the government’s consultation leads with the proposed exception, and then asks some questions about how the opt-out system might work, it also considers some other copyright issues raised by AI. That includes the transparency obligations of AI companies; whether AI-generated works should enjoy copyright protection; and how individuals might protect their voice and likeness in the context of AI.

It also asks whether “current practices relating to the licensing of copyright works for AI training meet the needs of creators and performers”. That’s a question where divisions appear within the creative industries, mainly between individual creators and performers on the one side, and on the other the companies that often own or control the copyrights in their work, such as studios, publishers and labels.

Because, if the creative industries win the argument against the new copyright exception, and all the AI companies that use existing content are forced to the negotiating table with the studios, publishers and labels, can those studios, publishers and labels unilaterally enter into licensing deals, or do they first need to get consent from individual creators and performers?

Organisations representing music-makers within the music industry are adamant that individual creator and performer consent is required, and creators and performers in other strands of the creative and copyright industries are making similar arguments.

So, when it comes to the government’s consultation, we know the position of the creative industries regarding the legal obligations of AI companies. But it will be more interesting to see what everyone says in their submissions about individual creator consent.