“Check my grammar,” Tori Amos says, serious and sudden, when debating the correct use of “was” and “were.” “My mother just came down from the great pub in the sky and said, ‘Darling, check your grammar.’”

Though Tori’s mother, Mary Ellen, passed away in May of 2019, she hasn’t lost her keen understanding of conjugated verbs. (And in this case, she was spot on.)

More from Spin:

- WHO IS BELLE BLUE

- Diana Ross, 80, Announces Major Career Update

- Jelly Roll Jokes Fans Might Confuse Him for This Music Superstar

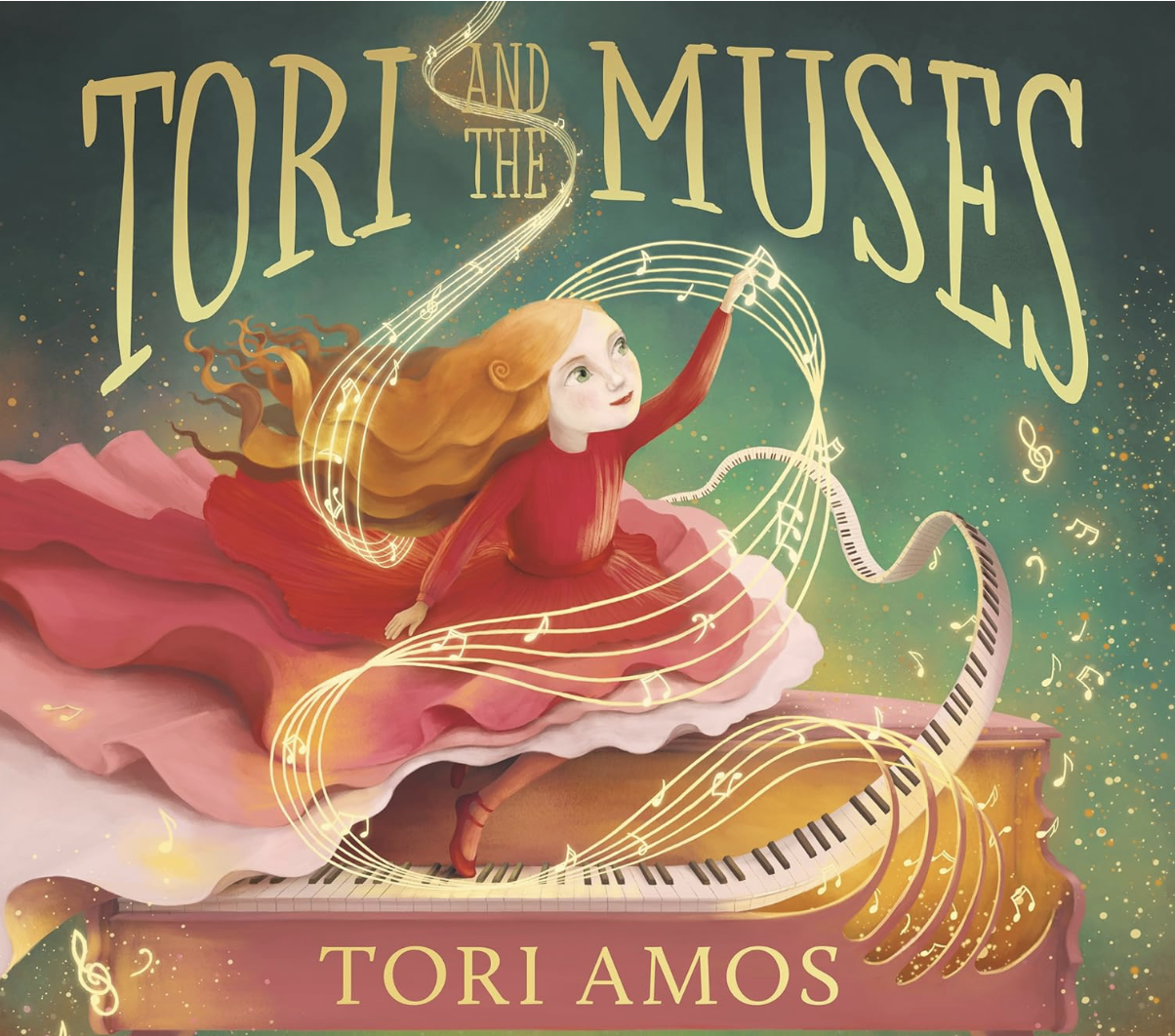

At the time, the discussion revolved around whether Tori designed her new children’s book, Tori and the Muses (released on March 4), with adults in mind. Her answer was: “Yes, without question. I recognized that there would be aunts and uncles, moms and dads, great aunts and uncles, grandmas and granddads, brothers and sisters reading this to younger children. There would be an interactive possibility there if it [were] constructed with that in mind.”

Tori and the Muses tells the sweet story of a fiery, pint-sized Tori as a child, frustrated and uninspired at having to learn music that’s “not any fun to play” for a recital. She argues with her father, telling him those “awful” songs are not what her Muses want her to play. When her father leaves, the Muses appear, as they always had since she was a baby, with “inspiration and magic.”

To know anything about Tori Amos is to know her colorful, constant relationship with the unseen: the color of sound, faeries, and her muses. Brilliantly, beautifully illustrated by Demelsa Haughton, the book follows little Tori as she—with a ginormous pink piano in tow—journeys around town to discover how other people “find their Muses.” There’s a boy who loves bugs, a baker frosting cupcakes, and a competitive surfer boy named Spike, who’d lost the joy he used to have “out there with the waves.” In the book, Tori leaves Spike wondering if he will ever find his muse again. (And turns out to be a character that resonates, not surprisingly, with many adults.) Tori and the Muses has a very happy ending, with Tori’s dad seeing the light. The story (accentuated by a gorgeous nine-song soundtrack) speaks to anyone feeling they’ve lost the spark that’s uniquely special to them.

Inspired by Tori’s real life—a child prodigy who, at the age of 5, won a full scholarship to Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory of Music—those actual early years were, naturally, not a fantasy story. Her 2020 memoir, Resistance: A Songwriter’s Story of Hope, Change, and Courage, bravely recalls the rough and sometimes gut-wrenching road to becoming one of the most groundbreaking artists of her time. Having been kicked out of the Peabody at 11, she went to work playing nightclubs at 13, a decision led and designed by her father. “It’s no secret. We had a complicated dynamic. That is not a secret,” she tells me. The children’s story, appropriately, highlights the love between them.

Tori and the Muses might be a story of learning and connection, inspiration and music, but for anyone who’s seen her on tour, you know it’s not too far-fetched. Wherever Tori goes, she’s sharing her magic.

This week, she’s traveling across the country to meet the people who love her and her message. “We are only culpable for the things that we are doing or have done,” she says. “There are some things right now occurring every day that are out of our control. What is in our control is the question, and that’s where I’m focusing my attention.

“Now certainly isn’t the time to not hold a safe place for people to gather. This is not the time for that.”

Did you learn anything about yourself as a child from working on this book?

Oh, yes. We touched on it in the book about the recital and the boring music homework. In my real life, it was much more extreme in that being at the Peabody Conservatory at 5, being able to play the whole Beatles catalog way before then… Of course, teaching a young budding musician how to read music. How they went about it was to take away all this glorious music and force you to play “Hot Cross Buns,” “Three Blind Mice,” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” to read.

That was 1968, but then this magical thing called music, it seemed to me at the time, became a punishment. I was able to play all this, and then I was punished with these horrible, not even music exercises—that were no fun. Nobody had the wherewithal to come up with ways of teaching that could be fun. It took a little while, I don’t remember the timeline. It was well over a year, but then to get into the Bach music for children and the Mozart music created for children to learn how to play, which then began to engage me again.

You felt like Bach was fun? That was fun?

Oh, yes. Of course. There is not a time when Bach is not magical. It can be dramatic. It took a year of torment, which when you’re five, a year’s a long time.

What the Beatles were doing in the ’60s and the impact they were having on music, it’s hard to explain right now. Nobody had heard anything like it before. I actually got kicked out of the Peabody, because I wanted them to teach the Beatles in theory classes. Someone had said, “Nobody will know who they are in 30 years.” I was 11 at the time, and in my response to that I just said something very sassy and smart. “You old stupid dodo,” you know nothing. I lost my scholarship and got booted out at 11, but then I turned pro at 13.

Before you wrote this book, and even before 2020’s Resistance, did you ever reflect on yourself as a girl and think, “What did that little girl want?” Maybe…have sympathy for her?

Yes, of course. I think she went through some stuff. That’s for sure. I think writing this book was an alternate reality with some of the facts of me as a little girl included in this [story]. The faeries and the muses are part of that truth. Dad has a turnaround in the book, which in actuality my dad didn’t have that turnaround. He became more of a stage mother, which on one hand it’s fair to say that I might not have been able to unlock certain doors without his tenacity. We will never know. We won’t know.

I became a professional as a teenager and honed a skill by playing for years and years and years and years in piano bars, which of course affected my development as a live performer.

A lot of us, as we get older, we are doing a job. For some of us, our passion becomes that job. And as much as we may love it, we can lose that curiosity. Sometimes, we lose the muses. We become like the Spike (surfer) character in your book.

There are a lot of Spikes that have written me letters. The Spike arc is very much a real narrative that people live through. I was driven to tell that story because I have gotten so many letters over the years that will say, “Well, I went out walking for weeks and couldn’t hear the muses, see the muses.” I believe in my heart everybody has them, but we don’t always know how to find them or how to receive them, especially if we’re looking for someone else’s.

I have a friend, he’s in his 40s, and he has discovered plants in the last five years and in Brooklyn, has a true green cornucopia growing in his Brooklyn apartment. He’ll take cuttings from when he comes to visit me in Florida. He’ll take cuttings from my garden. I’m not the gardener, but he’ll take cuttings and then grow them in his apartment in Brooklyn and show me how they’re growing. It’s just unbelievable. He has discovered in his 40s that plants are his muses, along with gemstones. This has been a discovery over the last five years.

It can happen later on in life. It doesn’t have to be that you figure all this out when you’re a child. Sometimes, [the muses] don’t appear to us until we try different things and realize, wait a minute, like Anna [a character in the book] discovered, ingredients are my muses. They speak to me.

What can we do when we feel the muses have abandoned us, as they did with Spike’s character?

I understand and that’s why I wrote him in because he doesn’t have a resolve yet. My question about Spike is… I’d love to have the opportunity to explore him more as a character because I wonder if Spike has to do something for someone else, not for him, to hear the waves again, to hear the mermaid speak.

On the record, there’s a song called “Mermaid Muse Speaks.” Spike can’t hear that. He’s lost his ability to be one with the waves because he wants to W-I-N. He can’t be O-N-E with the waves. When you want to conquer the ocean, then you’ve lost your alignment.

Sometimes it’s in the surrendering. That’s what I think we have to do…be open. My muses could be anything. Sometimes I think, we think, it has to be the cool thing. My muses have to be the coolest. Then you realize, wait a minute, maybe they’re snakes, maybe they’re reptiles, maybe they are sharks.

Sometimes we want our muses to be something different than they actually are.

Is it true that you were diagnosed with synesthesia (a sensory condition that turns sounds into colors)?

Well, a variation on the theme. I wouldn’t say that it’s a classic definition. It’s more loose than that. It’s not like… “That cord is orange.” That’s not how I roll. I would say that I’m an outlier with that kind of thing, but color visual shapes, a lot of times I’m describing to the sound men, I’m showing them pictures of glaciers. I said, “I want this EQ here sounding like this. This is what we’re doing. Look at this picture or look at this shape. I was showing all the musicians to make the music for Touring the Muses. They all had drawings of the book, and I walked through the story with them so that they had the reference points. For building them out, for example, the idea was we were literally going to build a mountain with sound and start with the lower register of the Bosendorfer.

We begin building that mountain from the World Wide Web, the mushroom network underneath the mountain. That’s where we’re beginning in that low register of Bosendorfer. The musicians all got on board and began to understand that. Then we get higher and we build an icy lake. Sonically we’re building that icy lake where we can skate, and then we go higher and find out how clouds can taste. Then we go even higher where we can touch the moon. The music is sonically doing that.

My visual world is not just about color, it’s about shapes. It’s about building a mountain or crawling through the swamp, and what does that look like? What does that feel like? What does that smell like? I’m working more on all the senses than just color.

What would your advice be to somebody who struggles with embracing their differences?

It’s in the uniqueness where you begin to recognize who you want to be and allow yourself that self-discovery and try things. It’s giving permission to have the freedom to try things. To grow those plants or not grow them [chuckles], and the freedom to try this or try that or take these pilgrimages. Expose yourself to the desert. Expose yourself to the mountains. Expose yourself to a city. The main thing, though, is to be present with it, that you’re there with ears open. You’re listening, and eyes open.

How important are muses now, today, in the world we live in today?

Right now, the muses are not contained by any leader, by anyone. That is a twisted fantasy. If somebody thinks they can contain the muses, they can’t. Now Stalin had gulags for writers and creators and contained them that way physically, but the muses can’t be. Now, some of our world leaders might have some twisted kink that they can capture muses but in reality, the way I see it, the muses are not bound by the laws of this earth. They’re infinite, they are not finite. That is something we can choose to open ourselves into that light.

How? There’s a lot of darkness.

There is. There’s no question about that, Liza. That, we can’t control. That is out of our control, the devouring darkness. I’ve said before, the only way to deal with destructive forces is to out-create them. That is the only way that I have found.

Plant your plants. Write what you write. Make your cookies. Bake your bread. Paint your paintings. Hike your hike.

Take care of your own backyard and feed your own soul because this is self-care now and self-preservation, and finding ways to do it, and finding those in your life who will nurture that.

How important are the arts in times like these?

That’s the thing that saves us and documents the time in a way that challenges all the artists themselves to have to think differently, especially when we’re in scary times when rights are being taken away, left, right, and center around the globe.

I did this book signing yesterday and met with 500 people. I’ll be doing that every day, but today (Monday), through Friday. I’ll be meeting more people with more stories. Of course, there is a lot of scary going on out there. I recognize that, and people are in overwhelm on how to react because some people’s lives are being absolutely personally affected from their personhood to their livelihoods. I feel like the artist, if you’re being called, then you’re being called to offer what you can at this time. It’s how you want to do that. It’s how.

For instance, I wrote and put out Resistance at a particular time. It’s out there. Would I put that out right now in that form, in that way with the times we are in? That is not the work I would choose to put out.

It’s out there. It lives. It exists, and it’s true. It holds up. In these times, we have walked into a situation that is very dangerous, that is very much about from what I see, retribution and persecution. I am not mentioning names.

Right now, the work is coming in the form of encouraging people to find their power, and that power is with you and your inspiration. When people become despondent and blue, then they’re not creating anymore. Then they’re being controlled by a dark frequency instead of recognizing that they’re, “Yes,” without question. There are dark frequencies all over the globe, but there are pockets of light.

We must go to that fire, sit around that fire, sing our songs, beat our drums together, hold hands, and support each other. That is the work, that is the refuge, and that is the medicine. That is what the muses are telling me.

Some people, Liza, are being called to write about things literally. They are being called and they are doing it, and that’s very courageous. They feel like this is what I’m supposed to be doing. Other people will find other ways to give and share and never underestimate a lemon tart.

Sharing your gift and the kindness of that and the power of that. There are people that are feeling isolated. That’s the message I heard last night [at the book signing] and I suspect I’ll hear as I cross the country. I’m also getting a sense from some people that, I am here, I am on this planet at this time, there must be a reason, so I’m not going to sleep through it.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.