Amidst our people here is come

The madness of the dance.

In every town there now are some

Who fall upon a trance.

It drives them ever night and day,

They scarcely stop for breath,

Till some have dropped along the way

And some are met by death.

Straussburgh Chronicle of Kleinkawel, 1625

On his last night alive, Australia’s doof-master goes hard. Spiro Boursinos knows no other way. Forty-five years old, few think he will ever change. There have been plenty of opportunities for humility, sobriety, contrition. He let them pass. If anything, it is getting worse. The booze and coke; the paranoia and aggression.

More from Spin:

- 5 Albums I Can’t Live Without: Warren Haynes

- Update: Neil Young Changes Mind, Will Play Glastonbury Fest

- Rico Wade’s Shower Inspiration and More Tales of How Outkast’s ‘So Fresh, So Clean’ Came To Be

On his last night alive, the music promoter is living with his mother. He owns nothing, is circled by creditors, has even sold the name of his festival to some kid. His friends and family say this is proof of his noble indifference to money – that he lives for nothing but staging parties and making people happy.

On his last night alive, Boursinos can almost touch the 25th anniversary of his event – the dance party Earthcore, the original Aussie bush rave – or “doof” if we’re talking Strayan – that draws thousands upon thousands of people out of cities around Oz and beyond on road trips deep into baking hot farm country to lose their minds in a communal ecstasy of dance.

He loves talking himself up. Loves spinning myths about his originality and influence, Australia’s – the world’s – wild maestro of doof. And the 25th anniversary event is just weeks away. At least, it is advertised as such. But its notoriety has made securing a venue difficult and a location is yet to be announced.

Yet on his last night alive, he is out celebrating getting sites for Earthcore just in time for next month’s jubilee doofs. Boursinos is at the Antique Bar, in Melbourne’s inner south. It’s Friday evening. He hits the bar at about 6.30pm and then for several hours drinks bourbon and coke, and does the other coke.

Friends come and go. When one of them buys another round at about 2am, Boursinos says he doesn’t want the drink. His mood plummets.

Now he’s behind the bar, screaming for cops. “They’re coming to get me! Call the police! Call the police!”

Boursinos himself rings 000 (Australia’s equivalent of 911), pleading with the dispatcher for police. “I’m about to get fucking killed,” he said.

He rings again: “I’m going to get killed outside.”

He rings again: “I can’t go out the front.” And again and again.

Looking for something to wield, he holds a water bottle up until a barman pulls it away, and then snatches Chivas Regal from a shelf to defend himself with – only for that also to be taken off him.

“You need to lock the door!” he yells, holding a stool in the air and then getting disarmed. Boursinos sprints behind the bar. He calls triple zero again, before grabbing a bottle of lychee-flavored French liqueur and breaking the front window with it.

Soon after, forensic officers of Victoria’s Major Crime Scene Unit and members of the Homicide Squad are at work, picking over the Antique Bar.

For a long time Spiro Boursinos had lived like a Scorsese character: ambitiously and destructively lawless. He was one of those men whose death is remarked upon in newspapers with the adjectives “colorful” and “polarizing”, insipid words that only hint at the unusual and intense disorder. Even his friends felt compelled to qualify his virtues to reporters.

Still, there were effusive tributes.

Dance-party collective Melbourne Raves offered its praise:

Larrikin, misfit, cultural innovator, marketing genius. Love him or hate him, Spiro Boursine [the spelling of his name varied] shaped the landscape for outdoor electronic music festivals, spurring a national pastime of extended dirty weekends … and in the process making extreme outdoor dance-floor escapism into a global phenomenon … Earthcore events weren’t just good parties, for the revelers and crews involved, they were life changing. Hippie level ascension to the max.

“He created a subculture in Australia that turned into one of the biggest alternative community followings that I think Australia’s got within the dance scene,” his old colleague and friend Gary “Binaural” Neal told The Age. “I mean, it created dance, it created fashion … it became a lifestyle for many, many people. Without Spiro, we wouldn’t have that.”

A long-term DJ friend of Boursinos’s speaks of the other side of the movement: “Sure, you’ve got hippies and peace and love and all this shit, but it’s run by drug dealers. [It’s] the most controversial, back-stabbing piece of shit scene you’ll ever find. It’s a business, like any other. The whole peace, love and all that sort of shit – it’s Santa Claus.”

This is the story of an ascension, followed by a long and bizarre decline. So luridly shambolic was Boursinos’s life that those who knew him warned me that his story would be hard to tell. They were right. There were too many lies and legends. Too many people too ashamed, suspicious, or fearful to speak. Then there were those who had made peace with the madness, boxed it up, and refused to open it. And across all of this fell the shadow of organized crime.

In 1992, Spiro Boursinos flew to Britain to experience its rave culture.

Or at least he said he did. Boursinos said a lot of things. Old mates of his tell me it never happened. Let’s just say that one can see why he wanted it known that he was partying in London back then: it was a fabled time and place for the rave, and a good place to steal some mythos. “I took the warehouse rave scene from the UK and incorporated it with the Australian bushland as a backdrop,” he told Vice in 2015.

The next year, aged 21, he staged his first Earthcore event – a small, cheap and unauthorized dance party on Mount Tanglefoot, in Victoria’s Toolangi State Forest. He did so with the help of Pip Darvall, a geology student he’d met at a Melbourne rave – a man more gifted with logistics than himself. A few hundred people came, and before their priestly DJs they tripped in the forest.

Having developed a taste for bush raves, Boursinos and Darvall got busy. Made flyers and posters. Arranged DJs. At warehouse raves in the city, Boursinos spread the word like only he could – with insistent, coercive excitement. By 1994, the call was issued to fellow freaks and psychonauts: Abandon the city! Shed your suits! Come party in the bush!

And the pilgrims came. Slowly at first, then in a rush. They came in convoys of old cars and caravans; they transformed their truck’s cargo trays into lounge rooms. They came with punk’s DIY ethic, and built giant sculptures from wire and spent televisions. They made campsites that smelt of weed and incense. They danced for days to psy-trance – intolerable to my ear, but blissfully incantatory to the mind properly bent to it. They swallowed LSD and E and bathed in mud and touched the face of God. They created a joyous spectacle, a carnival, an escape. By the late ’90s Earthcore was hosting up to 15,000 people.

Unlike the fabled British parties, these ones were legal. They required permits, and Darvall was the man to get them. “The logistics of putting something like this on were very challenging,” he says. “One of our particular successes was that once we got large, the events were legal, had all the appropriate permits, insurances and so on, so we couldn’t be shut down. As a result, I became a backyard expert in Victorian planning law. The regulations are … onerous, yes. But also sensible.”

Boursinos, Darvall says, had different talents. “He was ferocious at marketing, always pushing and pushing and pushing. And a lot of our success was due to that relentless marketing. We were regularly on page three of [Melbourne street press] Beat and InPress – unheard of for a company that spent the amount on advertising we did. It was very little. Even in our heyday we spent very little.”

As the punters arrived in their thousands, so too came journalists, politicians, cultural theorists and drug dealers. To some, these new arrivals were symptoms of rot – parasites attaching themselves to a dying host. The authentic doof – an onomatopoeic term taken from the heavy bass drum kick: doof-doof-doof-doof-doof – should not have a long life expectancy, they said. Doofs should be cheap, spontaneous, illegal – aloof from the realm of capital. Was Earthcore even a doof if it required the state’s permission?

Darvall was sympathetic to the hippie elements that poured in, who, in their chemicalized neo-tribalism, in turn drew liberal arts academics eager to contribute to the field of Aussie doof studies.

In a 2000 doof-paper published in the Journal of Contemporary Religion, Australian anthropologist Des Tramacchi, now a psychonautics instructor, writes that “The location of doofs in an ecological environment promotes a sense of linking the doof community to the landscape and allows the occurrence of spontaneous mystical bonds with nature.”

Another Australian boffin of doofery, Susan Luckman, now Professor of Culture and Creative Industries at the University of South Australia, published a 2003 paper titled: “Going Bush and Finding One’s Tribe”, In it, she writes: “Psy-trance-inspired doof has furnished Australia’s alternative party people with the vehicle par excellence by which to realize the dream of PLUR (the early rave motto which stands for: Peace, Love, Unity and Respect), and community.”

Australia’s doof theorists of the noughties had their American counterparts, including Scott Hutson, now Professor of Anthropology at the University of Kentucky. In a 2000 paper titled “The Rave: Spiritual Healing in Modern Western Subcultures”, Professor Hutson explains that the experience of embarking on a “technoshamanistic voyage” – getting high and dancing all night – seems akin to experiencing paradise: entering a timeless land of perfect and total joy, a pre-sexual age of innocence where there is no social discord, no differentiation between the self and other.”

If an Olympics for hyperbole were held, middle-class ravers and their cheering ethnographers would be highly competitive. And Aussie ravers were principally middle-class, unlike their UK forebears in the acid-house scene who found relief from Thatcherite Britain in unauthorized takeovers of disused industrial buildings – and in their own neurochemistry.

The spectacle of thousands of the young and beautiful raving night and day in the heat and dust of rural Australia drew international attention. In 2000, BBC TV sent a reporter to Earthcore. He found, with the genial faith of the travel writer, that “Easter means 3000 people follow the transcendental trail into the Australian bush in search of a tribal gathering.”

Three years later, Victorian politicians made their own excursion. Members of the Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee, they spent a day – and night – at the bush doof as part of their Inquiry Into Amphetamine and ‘Party Drug’ Use in Victoria. In their 730-page report, the committee writes:

Earthcore to some observers gives the appearance of being a mixture of carnivale, dance party, music festival, ‘agricultural show’ and ‘love in’. There are also a diversity of stalls and booths on site. These range from vegetarian cafes, coffee stalls where the coffee beans were hand ground by the purchaser pedalling a bicycle, stalls set up by Greenpeace and the UNHCR, to ‘shops’ selling colourful and exotic clothing, glow sticks and other ‘raving’ paraphernalia …

For all the fair-like atmosphere, these ‘sideshows’, while enjoyable, are very much secondary to the main attraction. According to the ‘ravers’, it is when the sun sets that the real fun and the raison d’etre of the festival begins – the dancing, the rave […] Many of the observations about the role of the DJ as priest, shaman or guru were being realised on this hot dusty night. The atmosphere created at Earthcore, according to those in attendance, very much paralleled the ecstasies, altered states or trance-like states described in the academic literature.

If some punters were irritatingly pious, many also had the time of their life. Much of Earthcore legend is scandalous, but there were better moments: Aphex Twin, a confounding but critically adored musician, DJ’d in ’95 with the ingenious use of a blender. The Orb and Perry Farrell followed. “If you look at some of the people who played Earthcore, they’re some of the top people in the world,” one punter told me. “I think that’s why the mythologising of Spiro is so great, because he pulled off these amazing spectacles.”

Lightning struck the main stage in 2004, but the show went on. In 2015, a great spiral of dust and convective heat moved across the festival’s paddocks, attracting stoned punters into its column as quickly as it attracted a nickname: Doofnado.

The parliamentary committee thought the logistics of these spectacles were “staggering”, and no doubt they were. Much of the respect for Boursinos derived from his crew’s acquittal of them – at least in the early days, before stories of inadequate toilets and fitful water supplies became common. Darvall told The Age in 2000 that they were creating a parallel universe. “We liken our events to creating a small city in the middle of nowhere, with all necessary services provided,” he said. “A normal city put through a blender.”

Spiro Boursinos wasn’t really political or spiritual, but he was happy to exploit others’ beliefs. In an interview with Professor Luckman, around the time that the Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee was on its fact-finding mission, Boursinos was comically unconvincing about the ‘philosophy’ of his event: “[There’s a] tribal element in the sense of it’s obviously back out in nature … So obviously there’s tribal roots to nature, so therefore there’s a tribal element.”

He would mostly abandon such pretense.

Years later, he told documentary maker Ryan McCurdy (for a still unreleased film): “We’re not a spiritual organization. We’re not an organization that’s saving the whales or, you know, the Stolen Generation, or whatever. We’re not that … There’s no ethos. No driving reasoning for it. Just go there on the weekend, unleash and regret it later – you know?”

Of course Boursinos wasn’t saving whales – he was too busy trying to save Earthcore from liquidation, despite his frequent boasts that he had created the country’s greatest, most enduring doof “brand”. He was fond of that word, and of his status as a quasi-historical figure. But the increasing size of the event, and its perceived compromises and commercialism, caused splintering. In 1997, a collective previously associated with Earthcore established the rival Rainbow Serpent Festival.

The great myth, according to co-founder Pip Darvall, was that Earthcore made a lot of money. “We never did,” he says. “When I was involved we made a basic wage, if we were lucky, and everybody worked other jobs. But of course people saw these amazing events, saw the huge profile, and thought, These guys are rolling in it. And that’s also part of the show – people want to be involved in something successful; they don’t want to be a part of a failure.”

In 2002, their company, Earthcore Events Pty Ltd, dissolved only to rise again in the form of Good Trix. Then, in 2004, two men went missing from the party – still known as Earthcore – held that year in Shepparton. One was later discovered wandering a remote track, dehydrated. But days later the body of the other man, Stephen Henshall, 22, was found face down in the Goulburn River.

Boursinos usually enjoyed being the face of Earthcore, but it was Darvall who represented the organization at the coronial inquest. “It was tragic,” he says. “The really difficult part is that someone died. Someone’s son died. It was a very traumatic experience for anyone involved. I was the witness for Earthcore, and spent three days in the coroner’s court being questioned. Afterwards I spoke to his family to express my sorrow. Our lawyers told me not to, but I did. How could you not?”

Darvall left Earthcore not long after. He tells me it had nothing to do with the drowning, and that he left on good terms with Boursinos. Darvall was by then a young father, which overtook his life as a party organizer. A geologist, today he’s the managing director of a gold, base metals, and nickel exploration company focused on a project in Uganda.

2008 was pivotal for Spiro Boursinos. Or it should have been, had he absorbed its lessons. Financially, Earthcore was bleeding out, and years of scurrilous behavior had cost him much faith. Accusations were numerous: Boursinos would advertise acts before they’d committed, sometimes without their knowledge, as a way of strong-arming their involvement. Artists were underpaid, or not at all – the same went for laborers and security. Onsite volunteers complained about not having the cost of their tickets reimbursed, and punters complained about not receiving refunds after their favorite artists withdrew.

There were serial complaints that the party sites were trashed, and multiple stories of masked men slashing the tires of punters’ cars that were parked outside the paid zone. There were strong and persistent rumors that the festival was part-financed by drug money. Police believed that drug dealers were using the event to launder money.

Meanwhile, Boursinos resented competition, and dismissed rival festivals as “Earthcore clones”. There was special acrimony between him and the Rainbow Serpent and Maitreya festivals, and for years there were mutual allegations of sabotage.

Then there were countless accusations of intimidation and verbal abuse.

Many told me of Boursinos’s volatility – charming one moment, threatening the next. By many accounts, including his own unsubtle quips with the music press, Boursinos was hitting the gear hard. He was also becoming increasingly aggressive, erratic, impulsive. He had no tolerance for criticism. His tirades to staff were matched by his abuse of punters in social media forums. His language was toxic. In one post, he published photos of two ravers – a man and a woman. “Just look at the quality of the haters here and it’s no suprise [sic] they all share a common characteristic. Fat and ugly. Just look at this monstrosity as a perfect example … And this fat pedo looking freak.”

Peace, Love, Unity and Respect. A former Earthcore colleague described that period to me:

“It wasn’t pleasant working for him … I used to think that it was just the music industry and it was normal. But when I ran my own shows I realized that it wasn’t, and that there were better ways of executing these events. [He] didn’t have any sense of conscience about the impact [he] had on other people. If you saw or heard some of what was going on, a lot of things in relation to women, it would make you feel sick in the stomach. For a long time I felt I had to move on, but I was committed to the Earthcore brand. Eventually I realized my own health was suffering …

“He was physically violent in front of me to a woman, pushing her hard against the side of a van at Earthcore 2008 … She reported it to police. He said if I didn’t back him up, the event will be shut down, so I backed him up … I guess I feel guilty in that I was complicit in a sense, supporting Earthcore.”

In 2008 a photo of Boursinos – his face bloodied, bruised and swollen – was shared online by the doof community. Most thought he’d finally received rough justice from an angry debtor. It was a theory sometimes encouraged by Boursinos himself, who never minded inflating his reputation as a wild man, though in an unreleased interview from 2013 he said the injuries were the result of a car accident.

A former colleague told me a different story: “The truth is, he actually fell out of a window while trying to escape his apartment, thinking people were after him. I know this because I drove him to hospital afterwards.”

Then there was the 2008 Earthcore itself. It needed to be bigger and wilder than ever, finances be damned. Boursinos was always chasing a dirty grandeur, a mix of respect and infamy, even if his pursuit of it burnt everyone close to him. But no respect would flow from the 2008 event. After being told their fees would be cut from the agreed rate, or failing to receive their deposit, more than half of the acts withdrew. The show went on, but if you wanted a refund you were out of luck.

That year’s festival was a catastrophe, and Boursinos lost the few financial backers he had left. He folded his second company, Good Trix, the one that had bought the debts of his first. Then came the big announcement: Earthcore was dead.

“I swear to God there will never be an Earthcore Global Carnival or festival in Australia again,” Spiro told The Age. “That’s it. I’m shutting it here, and that’s the end of an era. It’s exactly gone in the direction I wanted to take it. It’s grown to the size I wanted and became a brand name that virtually every Australian knows, and it’s pretty well known overseas too. I didn’t envisage it was going to become this big initially, but by about ’96 or ’97, I realized I’d created this freaky monster.”

For a couple of years, Boursinos roamed the wilderness. He spent countless hours playing online poker, surfing couches and nursing resentments. Not easily chastened, he dreamt of a comeback. Spiro the Phoenix. But his bitterness and irrationality were growing. His girlfriend became scared, and was frequently subject to long and abusive rants. She secretly began recording them. Later, she messaged a friend: “He isn’t well, I feel sorry for him. I love and care for him and will support him but I will no longer subject myself to his verbal abuse. Taping that stuff had been good because when I listen back in retrospect I see how shocking it is. I will be taking the voice recordings with me to a psychologist.”

Despite his behavior, she also said that “he has an endearing side to him that is easy to love. In essence, he has a good heart but there is some psychology thing going on in his brain that causes him to flip out.”

In 2010, Boursinos began working under the name Solar Empire from an office above the Royal Melbourne Hotel’s bar, booking acts for the venue and consulting for other events. I have read emails sent by Boursinos during this period. They are written with a thuggish hauteur, as if Pacino’s Tony ‘Scarface’ Montana had been transplanted to the world of music promotion – all machismo and ultimatums. In one, he demands that a colleague lie for him in order to conceal a romantic affair; in another he seems to threaten blackmail.

That same year, a colleague emailed Boursinos requesting an apology for verbal abuse. It’s a long exchange, and ends with the colleague writing: “If you really want the truth from me as a friend, I think you should get a real job and learn some more work skills in different fields. You did nothing but play poker for two years to hide from the truth and one day decided ‘Oh I had my little sleep and now to get back into it.’”

Boursinos replies, in part: “[I] never intend on putting on a multi-day event outside a major city not now not ever.”

Yet in 2011, he registered another company: Yellow Sunshine Pty Ltd. Incredibly, Earthcore was coming back. And once again, it would enjoy the support of the music press.

Two years later, the year of Earthcore’s 20th anniversary, it returned. Sitting behind a desk, imperiously holding a cigarette, Boursinos explained his change of heart to Ryan McCurdy’s documentary crew: “I lied,” he shrugs. “That’s it. Just lied.”

In 2013, Boursinos placed an advertisement in rural newspaper The Weekly Times, inviting Victorian farmers to lease their property to him for the event. He needed at least 500 hectares, a dam, and plenty of trees. In Pyalong, a town of just 660 people 90 kilometres north of Melbourne, local farmer Brendan Kelly had what Boursinos was looking for.

“2013 didn’t go too bad,” Kelly says. “That was my first experience, of course. But as the years went on, I got more and more experienced. Knew what to look out for. The first was like a birthing. But I had to make sure the locals were getting paid who are doing a bit of work. Local sporting clubs and contractors were doing all right. There was a bit of money coming into the area. Digging trenches, you name it. Mum and dad stuff. But if he fucks off to Melbourne, and you’re left in a small town with people who hadn’t been paid, well, that’s no good. So I’d have to ring up Spiro, and tell him this bloke needed to be paid. It got harder each year. They preach at the start that they’ll pay the locals first, but then they’re packing down and fucking off while the local blokes are still looking for the money.”

By 2016, Kelly’s faith in Boursinos was dwindling – as was that of a few locals in Kelly. There were those who saw Earthcore as just loud and druggy anarchy with little economic benefit.

“Spiro was high-strung and erratic at the start, but I didn’t see much of it initially,” Kelly says. “But second and third year, yeah, you witnessed it. Talking to people as if they were shit. He’d abuse people. Sends a bad vibe through the whole joint. Bad, bad, bad business and vibes. All bad. I persevered because the rest of us were doing all right.”

The day after Boursinos’s death, a curious obituary appeared on Facebook. In style, it reminded me of Hunter S. Thompson. In tone, it was unsentimental, and for the multitudes burnt by Boursinos, a counterpoint to the trade-paper hagiographies. The author had come to know Boursinos at 2016’s Earthcore. “To say his reputation proceeded [sic] him was an understatement, he was constructed of reputation and tenacity,” it reads, and continues:

In my eyes he was a reincarnation of Hoodini, an escape artist par excellence, and a high-octane dark magus whose bag of tricks included cocaine, promising to pay people, temper tantrums, but also dance floor alchemy. To say he started doofing feels silly. To claim that without him people wouldn’t otherwise connect ecstatically dancing to music in nature is like telling yourself at 12 that you invented wanking.

No funeral has ever deserved to have “I Did It My Way” played loud through a rig on some poor farmer’s property who has just realized he has bitten off more than he can chew when the check bounces.

I’ll remember him not through rosey rims that discount the darkness and boost the light, but in its entirety. I’ll remember the on-site waterboarding that was Earthcore as fuck, not in its political statement about imperialism but what it said about a party off its hinges, the embodiment of what happens when no-one is playing by the rules anymore, because he didn’t, and for that reason I tip my hat and pour out a big sip of my VB tinny at the Pyalong meat disco. There’ll never be another cooker like him, and that’s not a bad thing. RIP.

Waterboarding? I rang around, and sure enough others had heard the same thing. They described it like this: an Earthcore event featured four or five official stages, complemented by many unofficial ones – dusty campsites on the fringes, equipped with their own modest sound systems. It was here that you might buy, share, and ingest pharmacology. Or where you might retire, recharge or, in 2016, enjoy a little waterboarding.

I was given a number for the author of the Facebook post, who I’ve agreed to refer to only by his first name.

“Mitch, did you witness this waterboarding yourself?”

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “I did it myself.”

“You were waterboarded?”

“I partook for a LOL. It was purely voluntary. You could tap out. It was mainly for bragging rights, I guess. I was curious. There was a little bit of bravado, because they were timing how long people could last. I was on LSD at the time, and it was a little more traumatic than I expected. I just figured you could hold your breath, like you do under water, but you actually start breathing the water in – or you think you are. I lasted about 40 seconds.”

Never before had I spoken with someone for whom the question “How do I enhance my trip?” was answered with “Simulated drowning”.

Mitch continued: “Spiro knew it was happening, but I doubt he requested it. But it was happening the whole weekend.”

That year, Mitch and a friend agreed to paint some shipping containers for Boursinos in exchange for a little cash and tickets. Mitch says Boursinos was cagey and petulant in negotiations, then outright intimidating when they asked for payment up-front. Aware of his reputation, they thought that any money promised was money lost. “Eventually he dropped another $1000, but only with an all-caps email threatening us that If you don’t do the job immediately, my boys will come over and fuck you up. It was zero to a hundred. Uncalled for, over the top. We hadn’t even met yet. By the time we met on the dance floor, he was all happy and saying ‘It’s just business, boys’, and he was everyone’s best friend. But it was thinly veiled.”

Waterboarding wasn’t the worst thing to happen at that year’s event. Around 1pm on Saturday, November 26, day three of the party, punter Arthur Hatzistavros went to check on his friend Robyn Deans who’d been sleeping in her tent. He got no answer, thought she was still napping, and left without entering. Two hours later, Hatzistavros tried again. This time he unzipped the entrance. Deans was on her stomach. “I pushed her a few times and felt a dead weight,” Hatzistavros later told the coroner. “I pulled her over and noticed her face was blue. I ran towards one of the crew people and told them to get an ambulance.”

Deans, aged 43, suffered epilepsy, a fact shared with medics. One of them, paramedic Lawson Chan, later stated that, when they arrived, “I was a bit shocked by her presentation as I was originally told it was a seizure we were responding to. Her presentation was not normal and my shock was because it seemed she may have already passed.”

They confirmed her death at 4.46pm.

Boursinos panicked. He gathered his crew and told them a death had occurred, owing to an unspecified “medical condition”. That was the phrasing he insisted they use if anyone asked, and it filtered to the media. “I heard something [about a death] over our radio,” Brendan Kelly says. “I got no idea [how she died] … It was all about Spiro and his ego. He probably handled it wrongly. There was a lack of care or sensitivity. It was all about what it would do to him and his brand and festival. Could’ve been handled better, I’d say.”

Someone who knew Deans told me: “She was an old-school doofer. Rough, but really lovely … Earthcore – they just didn’t want to know. There was no memorial. No acknowledgment. No respect. A lot of people were very upset.”

I called Shannon Beveridge, a co-organiser of Earthcore and long-time friend of Boursinos. When I asked him to reflect upon how the event might have changed over the years, and whether different drugs created different atmospheres, he all but denied their presence at Earthcore. “A lot of people who went to Earthcore didn’t take drugs,” he said. “There’s a select few that do. But the last couple of years, we had drug sniffer dogs – nothing there. No one ever died at Earthcore from a drug overdose. No one.”

“What about Robyn Deans?” I asked.

“Robyn Deans died from a medical condition,” Beveridge says. “She didn’t have her pills with her.”

A “medical condition” – the same formulation I was told Boursinos had encouraged staff to use at the time of Deans’ death.

“How do you know, though?” I asked. “The coroner’s report was never made public.”

Beveridge paused. “My nanna used to babysit her. She wasn’t a drug taker.”

The coroner’s report on Robyn Deans was released to me a few weeks after I spoke with Beveridge. The forensic pathologist attributed her death to a “multidrug overdose” – specifically from ice, ketamine, and cannabis.

Deans’ epilepsy was not considered a contributing factor. The coroner used the phrase “multi-drug toxicity” to avoid the suggestion of suicide.

It was Brendan Kelly’s last Earthcore. The following year’s council application – which was late and inaccurately detailed – was rejected by the Mitchell Shire Council. “Even if Council did have authority to grant the request, it would be refused due to significant concerns about patron safety, illegal drug use, traffic management, security and noise that have not been addressed,” it stated.

But it would not be the last Earthcore – not quite. And it certainly wouldn’t be the last time Kelly heard from Boursinos.

Creditors were circling. Yellow Sunshine Pty Ltd was in trouble. Big trouble. Back in 2013, just two years after the company was founded, it owed many thousands to the Australian Taxation Office. From at least 2015 the company was suffering recurring losses. Later, forensic accountants would determine that Yellow Sunshine was likely insolvent in late 2016. It continued trading anyway.

Despite losing Pyalong and financial solvency, in 2017 Boursinos sought a dramatic expansion of Earthcore – parties were announced for Victoria, Western Australia, New South Wales and Queensland. Or perhaps the expansion was because of the trouble. Boursinos was an inveterate gambler, usually with other people’s money. He was always betting that today’s debts would be paid by tomorrow’s parties. Earthcore was a bubble that was punctured every few years, only to re-inflate itself with bluster, morphing ownerships and a compliant trade press.

Once again, something had to give. The 2017 Earthcore parties advertised 36 international artists, but the vast majority withdrew when they failed to receive either work visas, flights or payment. Tel Aviv duo Coming Soon were especially critical. On November 21, two days before their first Earthcore show, they announced their cancellation on Facebook from Singapore airport: “The reason … is because the owner of this festival didn’t pay us and didn’t even book a flight. After promising every week that he will send [payment] and after many [threats] of canceling us if we will not be patient … we never got treated like that ever in our 15 years in the industry and we will never work with this promoter ever again!!”

Before this, Earthcore had explained the cancellation by saying the act had double-booked itself overseas. But after Coming Soon’s post, and after the snowballing withdrawal of acts, Boursinos published a statement saying the WA, NSW and Queensland events were canceled, “due to a lack of ticket sales caused by a … smear campaign by international artist Coming Soon”.

This claim was made despite the fact that Coming Soon had only publicized their grievances days before the first event, and despite Earthcore’s website warning prospective punters weeks earlier that tickets were “down to the last few”. The spin was shameless. A lie would be published, then refuted, then deleted – only for another to replace it. To believe all the excuses was to believe that Boursinos was history’s unluckiest man – an innocent showman who somehow, every year, aroused the world’s destructive jealousies.

Three of the four events were canceled, but with a skeletal line-up Victoria’s went ahead in its new location of Elmore, another tiny town, north-east of Bendigo. There were some positive words online. There were also some bleak ones: “Left because I didn’t feel safe … everywhere you walked you saw people losing their minds.” And: “Organization was terrible … 36 artists pulled out, the ones people paid to see because the organizer hadn’t paid them. Juice heads were trying to fight each other, and people were littering left, right and center … It makes me sick.”

Boursinos was enraged by the negative media coverage, and resumed zealously patrolling the internet for criticism. There was plenty of it. In 2008, when Earthcore first collapsed, Facebook was relatively new, Twitter nascent, Instagram non-existent. But in 2017, each platform was now enthusiastically deployed against him.

Boursinos marshaled his own people to fight back. Suffice to say that if Earthcore critics weren’t threatened with assault or vexatious litigation, they were dismissed in the manner of an indignant schoolyard bully – as “losers with no lives”. When journalists reported on the shambolic finances, they were condemned as liars; when unpaid artists went public, they were slandered as drug addicts and attention seekers; when punters demanded refunds, they were brushed off as inconsequential “haters”.

But this was the least of it. One site became the special focus of Boursinos’s resentment – “Earthcore Memes”, an acerbic Facebook page dedicated to his mockery and exposure. And he became frighteningly obsessed with discovering who was behind it.

In August 2018, Brendan Kelly received a phone call from a man calling himself Jason. He had a message from Spiro Boursinos: “You and me need to sort out some shit, I can tell you that, pal,” Jason said. Having already received harassing calls from Boursinos and his associates – two calls a minute for half an hour, sometimes – Kelly was prepared. He recorded the call. “I’ll be there to see you in the next few days,” Jason continued. “And I tell you what, you want to fucking stop starting shit with Spiro ’cause you got no idea the army the bloke’s got behind him … You’re on your own out there, you motherfucker. You’ve got no idea the trouble coming your way.”

“Out there” was Kelly’s farm. The “shit” was the provocative Facebook page. To judge by the blizzard of legal letters, harassing calls and online abuse I’ve seen, Kelly was just one target. He denied he was behind the page.

“Who am I talking to?” Kelly asked.

Jason wasn’t the sharpest goon. He had used his own, undisguised phone number – and his real name. Kelly reported the threat to police, and they didn’t have good news: Jason had priors for assault. “[The police] said if he turns up, ring triple-zero immediately – or do what you have to do,” Kelly says. “Well, I was ready for him. I thought, If he comes here, it’s 50/50.”

So Kelly waited. Playing out violent scenarios in his head. Days passed.

“He rang on Thursday, and now it’s Sunday, and I thought, Where is this dickhead? When’s he coming?” Kelly says. “So I called him. And suddenly his voice was different. Confused. He was probably a drug mate of Spiro’s, and he was just sitting around sampling. He never answered his phone after that.”

Nor did Jason answer it for me.

On Kelly’s property there remain artifacts of the parties. The largest are shipping containers, and an old bus that served as the headquarters. “I looked into pursuing Spiro to get him to take his shit away, but he was so dodgy, changing companies and all this, that it was too fucking hard,” Kelly says. “All he’s got is a mobile phone, a laptop and half a pack of smokes. He didn’t have anything he could send you. By then he was slandering me online. Calling me a wife-basher. That’s another tactic, hoping people abort the mission. It works on a lot of people.”

Last year, ex-colleagues of Boursinos, and other aggrieved parties, created a private online chat group, to share stories with each other and a journalist (not me, though I was later given access). A friend of Boursinos infiltrated the group, and the names of its members were made public. “Here are the targets,” a Facebook post read. “If you are on this list you are in ALOT [sic] of trouble both sides of the law.”

In the months before his death, social media posts show Boursinos asking for the home address of one of the chat group’s members. To encourage people to disclose the information, he declared that the person was plotting to kill him. Boursinos never learnt the address, but what he did get was the “target’s” phone number – and their mother’s. He called several times a day. “It was classic,” the targeted person says. “He did this to dozens of people over the years, including ringing people’s workplaces and families.” Some of these calls were recorded. In one call to the person’s mother, Boursinos says: “Enjoy the infamy.”

One target went to the police. “I was fearing for my life,” they told me. “I wasn’t sleeping. The police took it pretty seriously, but they told me he was good at being threatening without being illegal. When I heard of his death there was shock, disbelief, but also a weird sense of prophecy. My best friend heard pretty fast from a DJ and they rang me to tell me it was real as they knew it would be hard for me to accept. And then, of course, immediately the conspiracy theories started – that he was faking his own death.”

You might think it strange that this person thought faked-death theories were inevitable. I would have thought so too, before I entered this weird twilight. One of Boursinos’s former colleagues told me that once he’d finally distanced himself after many years, Boursinos called and threatened to kill him. For a long time after, he slept with a machete beside his bed.

In April 2018, the forensic accountancy firm Ferrier Hodgson finished its preliminary report into Yellow Sunshine on behalf of creditors. “It would appear that the Company failed principally for the following reasons,” the report says. “Poor financial control including lack of records; poor strategic management of the business; inadequate cash flow or high cash use; and trading losses.”

There were two bank accounts visibly associated with the company, one of which contained $0.84 and the other overdrawn by almost AUD$88,000. Collectively, more than 80 creditors were owed almost$700,000. This included the ATO, which was owed at least$43,000, “but this amount may be greater due to unreported and unpaid taxation liabilities”. National Australia Bank was owed$90,000, after it had refunded that amount to punters who had successfully disputed their purchase of Earthcore tickets. These were the principal creditors, but there were at least 70 others owed $10,000 or less – many of them Pyalong locals.

It gets worse. Ferrier Hodgson concluded that Yellow Sunshine had likely traded while insolvent, and in their final report in March 2019 would say that it was for longer than they first realized. “Furthermore, the Director provided … two computers owned by the Company,” the report says. “[One] of the computers was missing a hard drive, whilst the other computer’s hard drive appears to have been wiped. A forensic IT specialist has confirmed that no electronic data could be recovered from the second hard drive.”

“I’m still fucked up by it all … I don’t listen to the music anymore. I’m in a dark place.”

Former friend of Spiro

When Spiro pounds on the Antique Bar’s front window with a bottle of liqueur until it breaks, a barman grabs him and gets the liqueur, but in the scuffle Boursinos winds up holding the snapped off stem of a wine glass. Bar owner Sam Faletti and the barman tussle with Boursinos, pulling the broken stem clear and then, with the help of a punter, drag him out of reach of the bartop and all its glassware, and force him to his knees. Spiro tries and tries to get up, but he is overpowered. After a two and half minute struggle he buckles and is now face down on the floor, legs thrashing.

Spiro shifts and strains to get free but under the weight and force of three men he can’t. Faletti, who is lying on Spiro, calls out asking when the police are coming, and tells Spiro that he’s safe, and that help is coming. The three men keep the pressure on for about two minutes. Spiro stops resisting.

Cops enter the bar, with Senior Constable John Petounas finding an unresistant man lying face down, hands pinned in front, with three men atop applying pressure to his back. Petounas places his boot on one of Spiro’s wrists as the trio disengage, and then he and his partner, Constable Rachel Hart, kneel and handcuff Spiro. Hart sees the stricken man’s hands twitching.

They roll Spiro on his side and check for breathing – which seems to be happening as his chest is moving and air seems to be moving through his mouth – but he is unresponsive, eyes now also twitching. Petounas radios for confirmation that an ambulance is inbound, but before it comes their patrol supervisor arrives at the bar and takes charge, ordering his officers to check Spiro’s’ lips, which are turning purple.

Patrol Supervisor Acting Sergeant Ward Randall can’t find a pulse, has the handcuffs removed, rolls Spiro onto his back and starts performing chest compressions. Paramedics now arrive, have Spiro dragged to the front bar where there’s more room to work, find no pulse, and no breathing.

The paramedics put Spiro on oxygen and stick pads to his chest, learning that he has not only experienced cardiac arrest, he’s asystole, meaning flat-lined — his heart’s electrical system has entirely failed. Defibrillators can work when the heart’s rhythm is haywire, but not when the heart has ceased operations. It’s classed as a non-shockable rhythm. When you hook someone in cardiac arrest up to a defibrillator and the machine goes through its scan, it will then announce: “No shock advised.”

With police continuing chest compressions, paramedics intubate Spiros but they can see that his pupils are fixed and dilated and his skin is turning blueish.

At 3.07 am, the Godfather of Doof is declared dead.

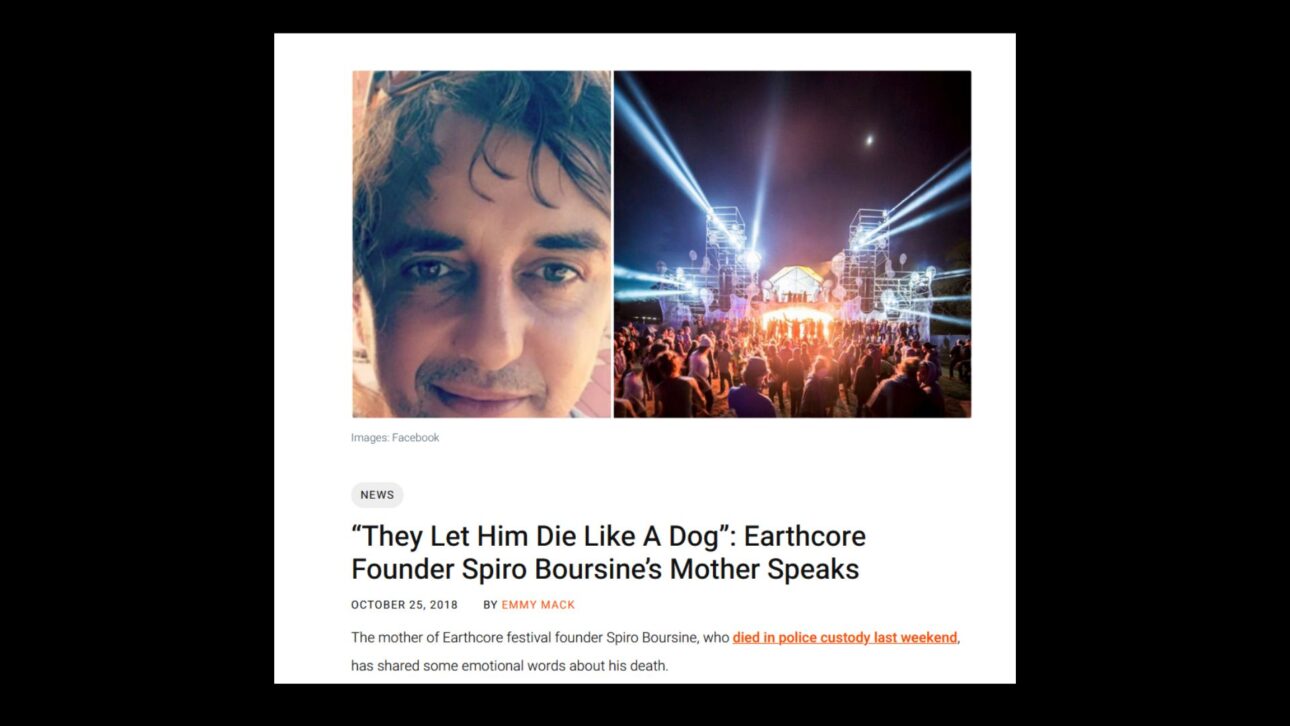

“They let him die like a dog on the floor,” his mother tells The Age.

Post-script:

“Basically, [Earthcore is] my life’s work,” Boursinos had told filmmaker Ryan McCurdy in 2013. “Initially, it was baby steps. But now I’m just running with it, like an animal. Hurtling towards the cliff, yelling out Sparta!”

Even in death, there was damage. A family had lost a son and brother; one of the men who had wrestled him at the bar fell into a depression and struggled to leave his house. Almost a year after his death, one of his former friends – the one who’d kept a machete beside his bed – was still bitterly haunted. “I’m still fucked up by it all,” he told me. “I don’t listen to the music anymore. I’m in a dark place.”

In May 2021 the Coroners Court of Victoria released its findings into the death of Spiro Boursinos. A coronial inquest was obliged by the fact that, just before his death, Boursinos was in the custody of police.

In her report, Coroner Jacqui Hawkins wrote: “I find that in the early hours of Saturday 20 October 2018, after consuming cocaine, Mr Boursinos experienced a drug-induced psychosis. The CCTV footage speaks for itself and revealed the tragic circumstances of Mr Boursinos’ death. The evidence reveals that Mr Boursinos appeared to be fearful of an unknown source. He appeared paranoid, frightened, and not connected to the reality of the situation.”

She went on: “It is clear to me that Mr Boursinos was not threatening any person in particular and did not intend to harm anyone. His actions were caused by fear and paranoia. However, his behavior was deeply concerning to those in his presence.”

Coroner Hawkins accepted the forensic pathologist’s ruling, made after an autopsy, that “Spiros Boursinos died… from coronary artery disease and mechanical asphyxia in a man using cocaine”.

Inside the black shirt that paramedics cut off Spiro to work on him was a bag of coke.

Coroner Hawkins found that the bar staff, who had restrained Boursinos during his violent psychosis, has acted in good faith and self-defense, and found that the police “also acted reasonably and appropriately in all of the circumstances and once it was apparent to them that Mr Boursinos had ceased breathing, they continued to actively provide him with medical assistance, even once paramedics had arrived”.

The report also detailed that, in the previous decade of his life, Boursinos had experienced several drug-induced episodes of psychosis which required hospitalization. And that: “Mr Boursinos had a past history of regular cocaine use which had resulted in the complications of serotonin syndrome, paranoid behavior, panic attacks and a cocaine induced non ST elevation myocardial infarct in 2014.”

In 2015, Boursinos was tasered by a tactical police unit after threatening someone with a knife. After his arrest, “Mr Boursinos informed [police] officers that he had used a large amount of cocaine and that he was intensely paranoid,” the report reads. “[Police] officers observed Mr Boursinos to look around the room constantly, not focusing on the conversation and saying that there were people after him. Mr Boursinos was sweating badly and was completely nervous and paranoid, asking questions constantly if the members in uniform were actually police.”

The “genius” and “cultural innovator” was a dangerously unwell man, who floated for decades on the buoyancy of his own will and persuasiveness – a persuasiveness he applied just as well to himself as others. He leaves behind a great flotsam of wreckage, not least the profound grief of his family.

This is an updated, expanded account of Martin McKenzie-Murray’s “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” which appeared in The Monthly.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.