Michael Lee Wood has been in prison for 47 years, serving a life sentence for murder. But that’s only half of the story. Because he’s been a constant thorn in various prison administrations’ sides, including being accused of trying to kill the warden at one of the many institutions that have housed him, which he denies, he’s been denied parole for decades. He’s also been incarcerated in isolation for a significant portion of his time, mostly as payback for publicly humiliating the Ohio Department of Corrections.

It’s not accurate to say he’s an uncontrollable inmate, because the reality is the authorities have all the control, and exercise it ruthlessly, even if he has proven to be a difficult and dangerous inmate. In prison, ultimately, the house always wins.

More from Spin:

- DEAR PATTI SMITH: Brooke Berman on Motherhood, Art, and the Fight to Keep Creating

- Tom Morello Taps Into ‘Rage’ Energy

- Left of the Dial: ‘The Current is the Heart and Soul of Minnesota Music’

Films and TV shows mythologize and often, perversely, romanticize prison. And so do magazine articles sometimes. The point of this one is to do the opposite.

I understand the fascination with glossing prison life, making it more of a caricature of what it’s really like. There’s the raw, primal nature of man vs man — that part is most definitely accurate, and easy to play out as mythic. Violence as currency, everything binary and stripped of nuance, uncertainty, indecision.

The reality is different. Not a thousand percent different, to be clear, but in many ways it’s much worse. It’s Shakespeare’s cold Hell. It’s (mostly) loveless and almost always insecure. At one point Mike talks about how prison is about adapting 24/7. Imagine if you in your life, whatever you do, wherever you live, had to be prepared to adapt to abrupt change and sudden violence every moment of the day?

I’ve known Mike, although never met him, for 25 years. He wrote a monthly column for my magazine GEAR at the turn of the Millennium, called “Letter From Prison”, about his experiences in the Supermax in Colorado, where the Unabomber, Timothy McVeigh and the Al Qaeda terrorists were sent. We have corresponded over the years, intermittently. He’s an intelligent man and never once in all that time has he expressed self pity or anger. And before emojis were ubiquitous, and certainly before he could have seen one, he used to end his handwritten letters to me with a drawn smiley face.

Last year he wrote and published a book Everything you wanted to know about Prison: But were afraid to ask. It’s the real deal, chillingly unadorned and unapologetic. So I contacted him through his intermediary and asked if he’d like to do an interview for SPIN, and he said yes.

At one point I asked him if he thought the prison system was humane.

“The prison system is definitely inhumane,” he said. “It’s a master at long-term isolation that affects prisoners emotionally and psychologically. There’s physical and mental abuse. No-one outside cares about inmates and we know it.”

As we start the interview, a guard is delivering his dinner to his cell.

So, what was for dinner?

I’m not on the regular meal. I got on the kosher meal.

Why, you’re not Jewish?

Everything is processed, there’s no real meat of any kind. I got off of that and got on the kosher meals, and that way you can get real meat and everything. Meals that are made on the streets [the outside world]. They can’t open them up or tamper with it or anything like that. They got to be sealed.

Tonight, we had beanie weenies, salad, bread. The beanie weenies had little inch-hot dogs in it with red beans, and mashed potatoes, and mixed vegetables. It’s pretty good.

You got a better meal?

Yes. The only bad is they serve you dry cereal and peanut butter and jelly every single morning. You don’t get a hot meal in the mornings.

What time is breakfast?

About 5:15. Sometimes five o’clock in the morning, early. I’m in ERH, Extreme Restrictive Housing [at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown], you’re locked down 23 hours a day. Tuesday and Thursday you don’t get out of cell at all. Then the other five days you can come out for one hour to get exercise, take your shower. That’s it.

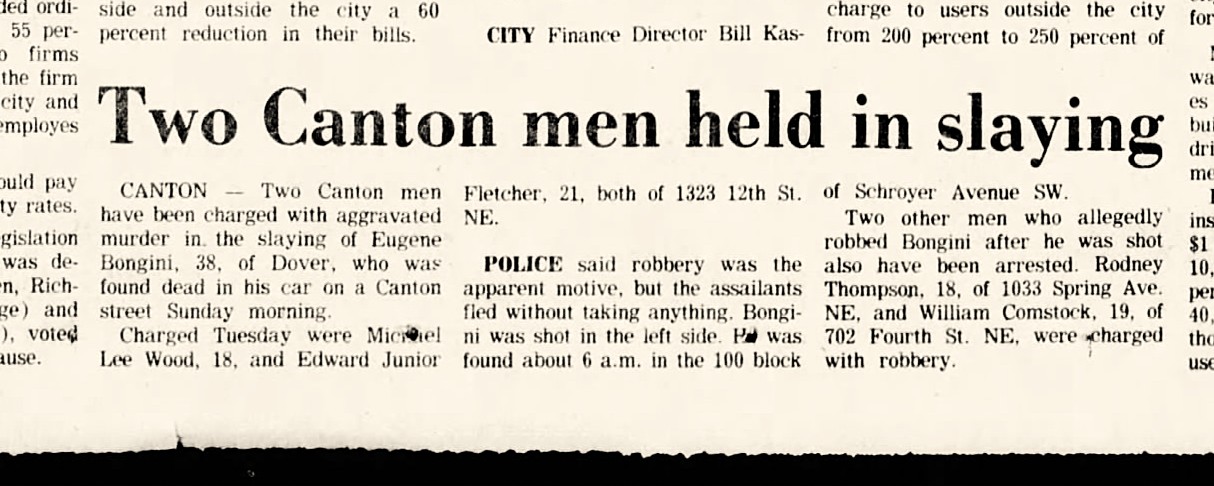

What were you imprisoned for?

Me and a partner killed a guy outside of a bar.

That’s ironic because I don’t drink, never did drink. I was underage anyway. We got life sentences out of it, went to actual prison in 1978. He did 28 years and kicked out. He’s been out in society now for the last 18 years. I’m going onto my 47th year in prison right now.

We went outside with two other guys, got into an argument. We went over to the car. I said, “Come on, dude. What’s up?” Didn’t have no plans of doing anything serious to them, was just going to pull a gun on them and rough them up. I had a shotgun, and my co-defendant had a pistol.

The guy was in the driver’s seat. When I pulled the gun on him, he panicked and started the car up. He couldn’t go backwards because my car was behind them. He couldn’t go forward because there was a used car lot and it had that steel wire across it. I said, “Where do you think you’re going? Well, you got nowhere to go.” Then my partner said, “Throw him away,” like that. Then I just shot him.

I pulled the trigger without even thinking. That’s why I’m in prison.

How do you feel about committing that murder?

You know what, I’ve told people my whole bit, out of everything I did in my life in prison, I was justified, I felt I was protecting myself in prison. But there’s one thing I do regret, and that’s pulling the trigger on this guy, because that should have never happened.

I was just a kid, a teenager. When I heard, “Pull the trigger,” I just shot. I can’t tell you why I did.

I never in my wildest dreams would’ve thought that I would’ve killed somebody that night.

You were in juvenile before that. Why?

I first went to juvenile when I was 12, for skipping school. That’s how they did it back then, in 1972.

What did you do to be put back repeatedly in juvenile?

Most of it was I would scale the fence and run away from it. I did that quite a bit, and then they would send me to a different one. I’ve been in some pretty rough juvenile institutions that were far worse, harder than some prisons I’ve been in. Kids are vicious and cruel and don’t know anything about consequences. Believe me, there was a lot of violence.

They had youth leaders in there. Like guards for juveniles. All the kids had to sit in front of a TV that wasn’t even on. You would have to sit there in silence. Everything was about silence. If you got caught talking, they’d beat you up. Sometimes, they would rough you up hard, man.

I remember one, little beady-eyed youth leader. Third or fourth night I was there, I was laying in my bunk to the back — there was a lot of kids in there, and most of them were in double bunk beds. At the door, they had single beds.

I remember him coming in and looking around and went over to one of the single beds. I still remember the kid, a light-skinned Black kid. This guy sat down on the bed with him, and they were talking and he reached in his underwear, pulled it out, and started giving this kid a hit. I was scared to death. I wouldn’t move. I thought he would see me and come over. There was a lot of that.

A month went by and we saw all these suits standing around. They said, “pack your stuff up. You’re going home.” All of us ran to the dorm, packed our little bit of stuff up. Guys that didn’t have rides, they were taking them home. They told our families that we did enough time. It was to keep everything quiet.

What was your first year like in prison? You were young, naive, presumably vulnerable. How did you survive?

Listen, when I first got convicted and they take you to the [old] Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio, it was cold. It was like a reception spot. They tore it down in the early ’80s. Right off the top, you got guys that are going to test you. Anyway, I stuck a couple of guys there. I stabbed a couple guys for testing up on me. Then, I went to another block that sends you to Lucasville, which is the max security penitentiary.

What I told myself going through the juvenile system was that I refused to be a victim. I wasn’t going to be taken advantage of, extorted, pressed, raped, none of that. I knew how the prisons were back in those days. There was no cameras in the hallways. There was no metal detectors. Having a knife was like a toothbrush. Everybody had one in their pocket and was willing to use it. Back then, the more people you stabbed or killed was the more reputation you got. That’s what it was about in prison back then, reputation.

That’s what I had to do because I was a young, pretty kid, man! I was actually skinny, too. Before I hit the plates, weights and stuff. As soon as someone got aggressive to me, when I knew, oh, man, this is going to get out of control, I got my weapon out, and I used it. That’s what kept me alive in prison, and it got me a reputation where dudes are saying, “No, leave that young kid alone.” They would go on to easier marks than me.

Then in 1989, we were in the gym and a big old thing breaks out. It’s all about this gang leader who was a bad gambler, and he owed a bunch of money. Rather than play and pay the money, he would have dudes stab them up and get them out of the way.

We were in there saying, “No, you can’t do that. That’s wrong.” Anyway, a big fight broke out. All said and done, the gang leader gets killed. Me, two of my partners, Benny Taylor and Benny Fields — Benny Taylor went to the streets, and he died of a heart attack. Benny Fields, he’s on the streets now, been out for 12 years — they indicted us for killing this gang leader.

We went to court and 45 minutes after a four-day trial, the jury came back and found us not guilty by self-defense. Went back to prison, and we got back to population about a couple of months later. We’re doing fine out there. Everything’s all right. Then about 9, 10 months being out, Benny, DT, and a lot of my friends got picked up on an investigation and were slammed in the hole. They were supposed to come and get me. Later I find out the white shirt told [the other guards], “Well, it’s time for us to go home right now. We’ll get him in the morning.” They left me out there.

That morning, I see something out my peripheral vision, and this dude is running. He’s coming up on me from behind fast. He’s trying to hide a knife in his hand. I pull up my knife, and he attacks me. Look, I’ll be honest with you, I’ve trained with weapons in prison because that’s what you did. You trained with yourselves, how to hold a knife. If you see a dude, how he holds a knife, you know the only way he can stab you and how long it’s going to take. You do this over and over until it’s monotonous, until you know how to use your weapon real good.

I get out on him. He ends up dying.

I never was indicted on it, though. Later on, some of the guards were saying, “Well, you weren’t indicted because the administration left you out there all by yourself. It’s like they wanted something to happen to you, and it happened the other way around. They don’t want to be put on the witness stand at the trial, so they’re not encouraging no indictment.”

Did you and your partners kill the gang leader?

Yes, I had to.

What is the code in prison, and how important is it?

The code? The code’s life and death. There’s a code that everybody must live by in prison. It’s things you can’t do and you can do. It varies from state to state. It varies from state to federal system. Obviously, the most obvious ones are if you get caught snitching, something’s going to happen to you real bad. If somebody steals your paperwork and you got a downward departure, which is you testified against your crime partners or something like that to get less time, something’s going to happen to you. If you’re in for child molestation, and even in my state, if you’re in here for putting hands on some real old people that can’t defend themselves, then somebody’s going to put hands on you and let you feel how it feels.

Almost like a moral code?

It’s a little bit different. Everybody gets their paperwork checked [by a prisoner] in the feds to make sure that everybody on the yard is in good standing. Now, of course, some people fly through, but eventually they get found out because dudes are always running checks, and especially when guys appeal. See, they might come in with false paperwork or paperwork that doesn’t say anything, and then if they appeal, all the dirtbag stuff they did comes out.

In prison, how are people supposed to behave?

How are people supposed to behave? Obviously, first thing is respect. You’ve got to respect everybody. You’ve got to be careful what you say. If you say the wrong thing — there are certain words that you can’t take back under no circumstances. For example, if you get mad and a dude gets mad at you, somebody might say, “Man, fuck you, you bitch.” That’s something you can’t apologize for. You can’t say, “Oh, I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have– ” No, you’re going to get killed or at least get stabbed up. It depends on who you’re dealing with.

You can’t call [someone] a motherfucker, you can’t call a dude a rat, a dick sucker, a homosexual. You can’t say that you’re a fag or whatever. Those are killer words. Those are words, if you’re trying to hurt this guy, he’s going to hurt you in return. If he doesn’t do anything, that’s going to reflect on him with the other guy, the other prisoners. Then they’re going to see him as weak. Then they’re going to take advantage of him because he didn’t take care of his business when he’s supposed to.

I know in my prison it’s the same thing with the guards — if a guard come in here and shoots you down and tore your cell all up, or he talks really stupid to you, you have to do something to him. You don’t have no choice. This is why: if he goes and does it to somebody else, that guy has every right to take your life or to put some steel in you, because if you took care of your business the way you were supposed to, he would have never had that done to him.

How often do people get disrespected? If everybody knows they’ll probably get stabbed, why does anybody ever do it?

They do it in the heat of passion, and then some guys just say things out of their mouth. Then they realize that they messed up, but it’s too late. There’s probably not a whole lot of disrespect going on because they know that, if I say certain things I’m going to probably end up losing my life on it or have to kill somebody about it so that I don’t get killed.

How did you become so respected and feared in the system?

I came in at an early age, and, one thing, I learned how to be just as vicious as the dudes in my environment.

I came in so young, Bob. It’s like being a kid. When you’re taught something as a kid from your parents, it just becomes natural.

Listen, violence was encouraged in prison back in the ’70s and ’80s. As I look back, I see my young brain just absorbed all this stuff around me. I’ve seen how guys are getting the respect.

The administration didn’t care nothing about dudes getting stabbed, killed, or anything like that. They didn’t start indicting people until the late ’80s, ’90s. The ’70s and all through the ’80s there were many, many killers in the joint.

How did it become a consensus not to mess with you?

From taking care of my business, anybody got in my face, I’d put the steel in them. I was just as vicious as anybody else. Then, of course, the couple of murder cases, and a couple that do see me as a nice guy. I was a likable guy, and so they would say, “Hey, this is a likable guy. He’s a smart and intelligent dude, but he will take your life if you get out there and do anything that you’re not supposed to be doing.”

Are you ever in danger?

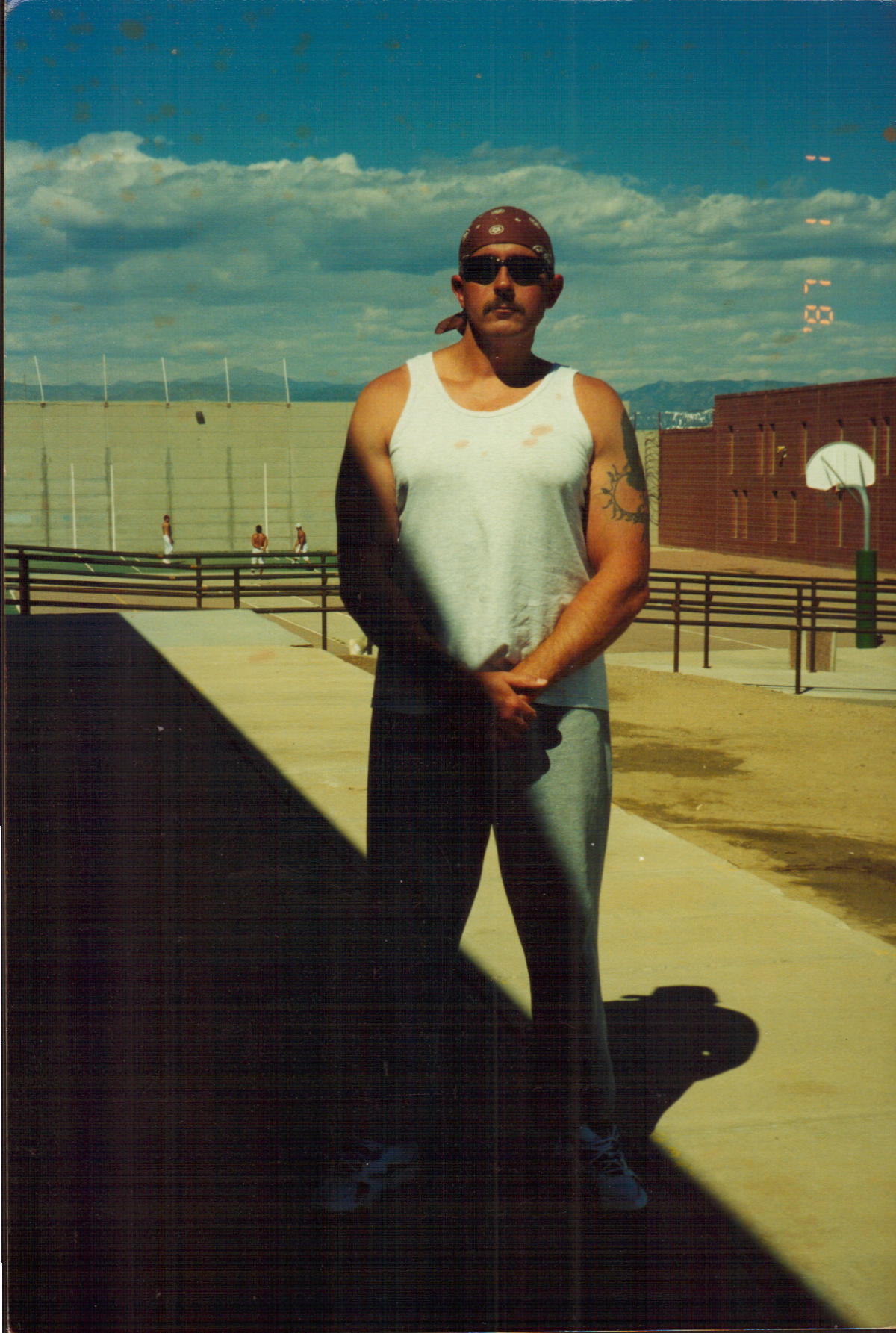

Oh, yes. Anything can work out when you’re in a knife fight with somebody, and I’ve been in a couple of them in Ohio. Then, when I went to the feds, I still had that reputation. I went to the Supermax, the ADX in Colorado.

There, I met a whole lot of good dudes that gravitated toward me, some high-profile dudes. Dudes generally like me. They understood my reputation and stuff and what I’ve done in Ohio.

When I was out at Victorville, in California, that was a gang yard. I took over the yard [as shot caller, more on that below], but there were gang members that were doing things crazy. Some gangs, that’s how they are. They think they can just do anything to anybody at any time and no consequences. I would pull up on them and tell, “Hey, listen. My name’s on the yard right now. What you’re doing– ”

There are gang members, and then there are independents. Independents are guys like myself who’ve never been in a gang before. I’d tell them, “Listen, if an independent dude did what you’re doing, we’d already beat him up and sent him on his way. That’s the last time I’m going to talk to you about it.”

Sometimes they do it again, so I’ll put my hands on them. I give the order to smash them off the yard, and I did that quite a few times.

When I got a lateral [transfer] from Victorville to Lee County in Virginia, I was walking to the commissary one day and I noticed that two gang members were posted up. I could just feel it. I knew a move was going to be made. They were members of the gang I smashed off the yard up in Victorville.

You had to turn your batteries in, in that prison. I had them in my mesh bag. When one started walking beside me, I was like, “Is there something you want to say to me?” and the other one pulled a knife out. I’ve seen that coming, I’d seen him reach in his pocket. I took the batteries and started swirling around to pop him in the head, and he ended up dropping the knife. The guards see it out in the hallway. They come out and spray us all down.

I get transferred to another Fed joint. There, guys with that gang snuck up behind me and hit me with pipes. 18 hours later at the hospital when I came to, the nurse was looking at me. She said, “Oh, you’re awake. We didn’t think that you were ever going to wake up.” I was like, “Well, okay.”

In the feds, you can sign what they call a Superman clause. When I got back to the prison, I told the SIS — the Security Investigative Service — I want to sign a Superman clause. That means they’re going to let you back out to population. You’re saying there ain’t nothing going on, that was a mistake.

They come to my cell and said, “We can’t let you out. A couple of people told us that if you come out, they’ll kill you or somebody’s going to get killed. We can’t put the warden under that pressure, so we just got to get rid of you.” They sent me back to Ohio.

Where you were accused of trying to kill the warden, at Lucasville?

Yes.

The warden comes to me and said, “That’s it. You’ll never see a general population again,” and I write to central office and tell them, “If you guys are never going to let me see the general population again, send me somewhere where I can start over.” They said, “No, that’s never going to happen. Forget about it. You’re there. Get used to it.”

I said, “Look, I’m doing a life sentence. If you think I’m going to do the rest of my bit in the control unit, your ass is as good as mine. You’re going to send me out of here eventually.”

They said, not in these words, “Do your best.”

I had a lot of control in the prisons because all my guys were in all these different prisons over the years. I started getting live ammunition, boxes of bullets. I didn’t want to get the real guns, just zip guns. You can make a zip gun out of basically anything. I would get stuff to build bombs — smokeless powder, black gunpowder, .22 rifle balls. The .22 rifle balls were the easiest, because you can set them off real easy rather than .38s. Then you’ve got to use a nail or something to set it off.

Anyway, I didn’t give them to nobody. I could have passed that stuff out to the whole institution and told everybody, “Here, have fun.” I never did that because I didn’t want to get people hurt that didn’t deserve to be hurt. I just wanted to embarrass the Department of Corrections.

I would let them find it in my cell, because I knew that I could get as much as I wanted. I wanted the Department of Corrections to figure, “Oh, this is his stronghold right here in Lucasville.”

They sent me to Mansfield, a new supermax area they opened in February 1991. One day, the guards were telling everybody, “lay down,” and the sergeant would come in and say — I remember this gray-haired sergeant coming in –- “lay down, you bitches. This ain’t Lucasville. We don’t pamper our prisoners.” I thought, who are you disrespecting like that, man? What? Are you crazy? He was like, “This is our prison.”

That went on for four days. Then, finally, I told a guard passing out lunch, “Go tell the unit manager I want to talk to him. We got to resolve this. When you come and pick the trays up, if he’s not up here, I know that he doesn’t want to talk. These doors, we’re going to set these doors out on the range.”

He just laughed about it and when he came back, he said, “I talked to him. He’s not coming. He got nothing to say to you.”

They had these 300-pound steel beds bolted into the floor in the cell. We ended up loosening the bolts, and then took them off and put the beds on the side to start ramming the door. Me and a couple other guys took the doors off. Then we came out on the range.

They sent a bunch of guards and got us down, and worked us over, set us outside the hospital.

Later, I got more bullets and stuff to build everything I wanted to build. I just shoved those into my mattress knowing that eventually they were going to find it once they do a shake down.

They get in, and they panic. “Oh, he’s going to kill us. He’s got live ammunition!” So they shipped me back to Lucasville. Then, about a week later, to Lebanon, Ohio. Put me on the top range all by myself. They put a special door in the back, six cells in the back, and moved me from cell to cell every day. Nobody else was up there other than the guards to watch me. I really couldn’t do nothing.

People might think this is far-fetched, but it’s the truth. The guard that came by, I talked him into letting me take him hostage.

How did you talk him into that?

That’s a trade secret there. He was supporting what I was doing, he brought me bullets and stuff. I say that now because 30 some years have went by. They think I got a real hostage and everything.

After I let him go, I get jumped on, beat up, and put in a cell butt naked with the window open. This was in March. It was snowing out. It was cold as I don’t know what. I’m in there butt naked with a concussion. They left a mattress in there. I’m thinking I got to keep warm because I got a concussion. I used my thumbnail to just rake it back and forth on this mattress until I could get a little hole in it. Then I ripped it open at the top and I crawled in it to keep warm.

About two weeks later, one of the guards took me out of there and put me in a cell. I heard one guard talking to the other one. He was like, “Yes, he took a polygraph and failed it twice. Then he came clean.” I just knew that they was talking about this guard [I took hostage]. Sure enough, for some reason, they asked him to take a polygraph.

Instead of him saying, “No, I’m not taking it. For what? I’m a victim.” He took a polygraph. I’m thinking, you can’t be that stupid. I think he did 13 months.

Did you have any intention of killing the warden?

No, I never had no intention of that.

I knew that the media like sensational stories. I was on the front page of every newspaper in Ohio. I knew eventually the Department of Corrections was going to get tired of it, because they had to explain how this one prisoner keeps getting all this ammunition, and bombs, and was breaking out of supermax cells.

They wouldn’t even let guards around me unless there was two or three of them because one would have to watch the other to make sure I wouldn’t convince them to do something.

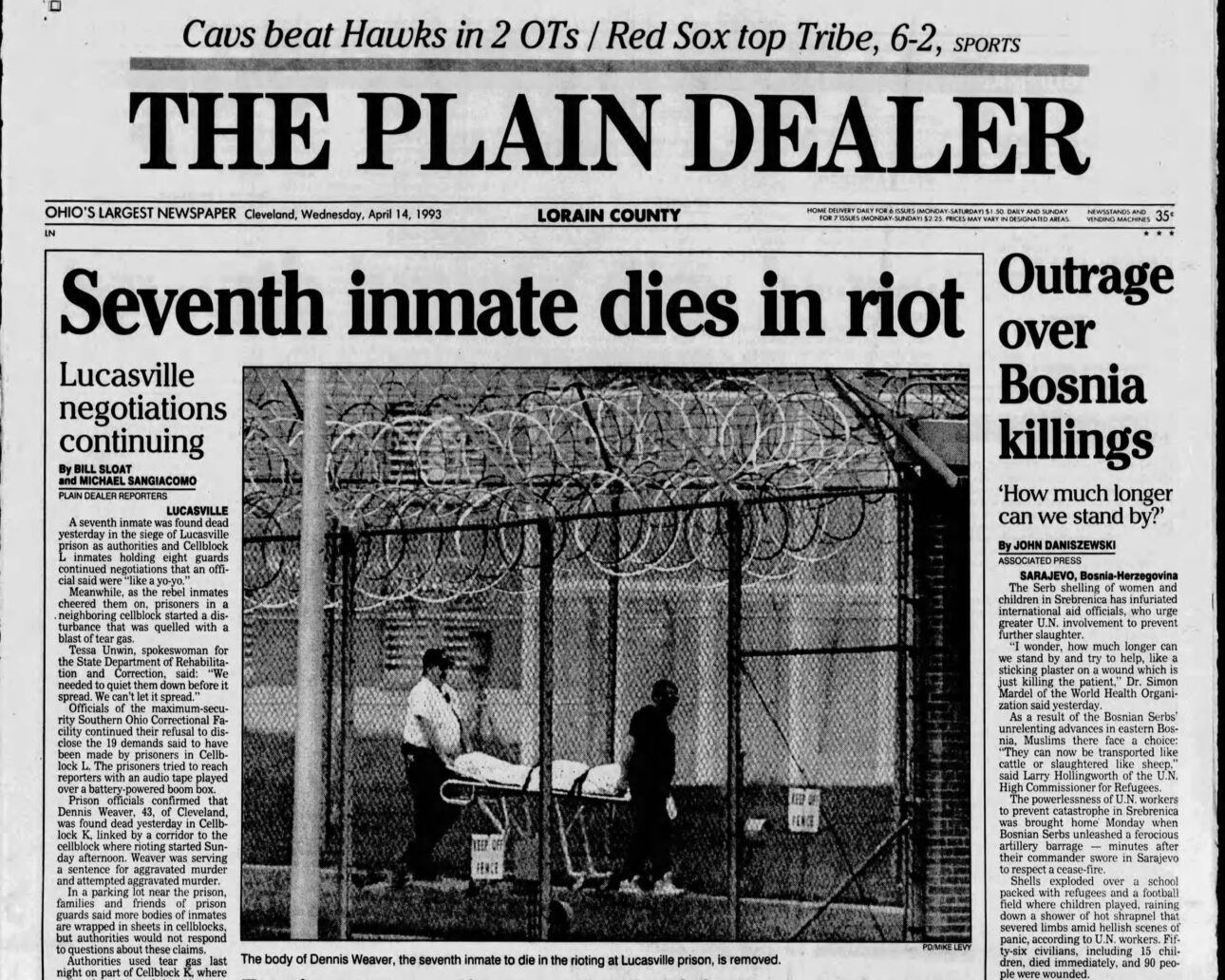

I got moved back to Lucasville. That was in ’92. Then the riot happened in April of ’93, the longest riot in U.S. history. They held the joint for 11 days.

Soon after that, I had another guard bringing me in bullets and other stuff. Then he left the block and was working in the hole, couldn’t get the stuff to me.

Again, stupid mistakes: There was a guy over there who was telling them how cool he was with me and my homeboys that were from Cincinnati where he was from. The guard said, “Hey, if I give you something, can you get it over to Mike?” He said, “Yes, sure. Whatever you give to me, I can get it to him.”

The inmate went and told the unit manager. Then, as soon as the guard brings it, he tries to hand it to the prisoner. The prisoner says, “No, just put it back in your lunchbox and your Igloo. Before I lock up, I’ll get it.” He gives a signal to the unit manager and they come in, find the bullets and stuff, and take the guard out.

I told the guards, “Look, there’s only two guys that I trust in prison, period. That’s my two main partners. Anybody else, don’t trust them. Don’t do nothing with them.”

Whatever happened to the guy that gave up the guard?

They took him out of Lucasville at midnight, put him in a van and took him to the Warren County prison, a protective custody joint.

When did you go to the Supermax in Colorado?

September 23rd, 1995. They sent some extradition agents that picked me up, and they drove me there. It was a couple days drive, two or three days on the road.

The guards that I was cool with were, like, “Man, even the governor’s getting on the director about why is this guy in the news and got all these bullets and stuff? Every bullet is a potential murder case.” That’s how they looked at it. I’m like, I could have gave bullets to dudes in three different joints, but I didn’t do that. I just wanted to embarrass the Department of Corrections into dealing with me.

I did, but even 30, 35 years it’s coming back to haunt me because these people slam me in this supermax unit here in Youngstown without me doing anything. They say it’s because of what I did all those years ago.

What’s a shot caller, and how does one become one?

A guy that has the respect of the yard is a shot caller. When I took over, my very first time, I was at Hazelton in West Virginia. The main shot caller on the yard, he was doing some messed up stuff and making some messed up calls. The guys wanted to rid of him, but he was a shot caller, and he had a lot of power behind him.

They came to me and told me about everything that was going on. Anyway, at the end of it, they all wanted to support me and needed me to be the shot caller of the yard. Because they were in their right and the dude was doing some messed up stuff, I said, “Okay. Everybody does exactly what I tell them to do. We’ll make this happen,” so they did. 45 minutes later, I smashed the shot caller off the yard and 38 of his dudes and took over the yard.

What does it mean to smash them off the yard?

Just beat, and beat, and beat him up. Everybody has to be blooded up to go off the yard in the feds. That’s mandatory. You got to have some blood. Nobody’s allowed to walk off the yard.

What is your authority, and what if someone defies the shot caller?

Well, first of all, a shot caller has total say on the yard. Whatever he says is law, and if anybody goes against what the shot caller says, he messes his whole career up. He can’t go nowhere else in the joint. He’s going to get beat up off the yard for one, and then wherever he goes, dudes are going to be waiting for him to come into the block, and they’re going to smash him on sight, so he’s not going to be able to stay anywhere.

Eventually, he’s going to have to go stay in the hole, or a special housing unit. Or he’s going to have to go to PC.

A shot caller, you have to make yourself available all day long. You’ve got to be out on the yard at least once a day for dudes bringing disputes to you, and they vary, and you determine who stays, who goes, how bad they have to leave. For example, nobody’s allowed to get smashed off the yard without the permission of the shot caller. Everybody brings him all the facts, and he decides, “Well, okay, you have a right to smash that guy off.” or you say, “No, he don’t deserve it. You guys are just in your feelings. He doesn’t deserve that. He needs to get disciplined in the field.” Meaning that in a lot of cases, they’ll take a guy and make him hold on to the top bunk, and then they’ll just beat him to his body. They’ll hurt him for a little while, and he can stay after that.

Why does the prison allow it?

They allow it because it keeps control of the yard. There’s a lot of guys that just want to create chaos and do whatever they want to do, but having a shot caller that’s in charge of the yard, especially when he knows what he’s doing, everything runs smooth because these guys know that if they step out of line and they violate whatever is not appropriate, they’re going to get hands put on them.

Depending on the shot caller, he can say, “Yes, he can’t get anywhere else.” That gets to other prisons, and when he goes to that yard, he’s going to be smashed off or worse.

The administration, especially in the feds, they want guys to be shot callers. Every time I went to a yard, they’d say, “Oh, you’re going to be the shot caller for this yard. We can see that right now.” They love that. The wardens and the security investigators, and the captain, they want a guy like me on the yard that can think, that can rationalize situations, and is going to do well in the prison, because it makes them feel safe. [Laughs]

There wasn’t a killing on the yard [at Hazelton] in the whole four years I took over.

There was a couple of fights. No matter who’s in charge, somebody’s going to get beat up or have bad paperwork and stuff like that. I made sure nobody was killed on the yard. When I went to Victorville, six months later guys started getting killed on the [Hazelton] yard, and there were lots of lockdowns because the violence was off the chain. One of the guys that was there came to Victorville and said one day the fellas were coming out of the chow hall and asked the warden, “why all the lockdowns for so long?” The warden responded “keep killing inmates on my yard and this is what the norm looks like.” An inmate said “If Mike Wood was still here, we wouldn’t have all this bullshit.” The warden said, “You’re right. Worse mistake I ever made was letting Wood transfer out.”

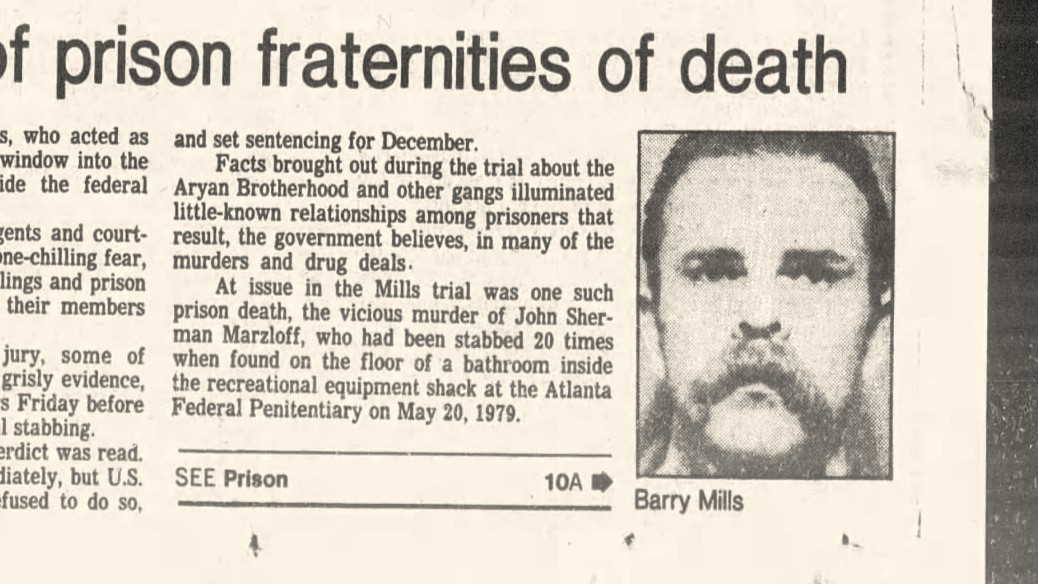

Victorville has always been an AB Yard, Aryan Brotherhood, since it opened up. When I got there, they had just killed one of their own for working with the administration. The administration took all of the AB off the yard and sent them to different joints. Maybe five weeks or so after that happened, I get a message from the dude that killed the AB guy. He said, “I got a letter from Barry Mills,” who’s the face of the AB. He started the AB in 1968 at San Quentin in California — he’s dead now; died maybe six years ago at ADX — Barry asked would I take the yard, would I hold the yard down for him?

I’m thinking, better to do things on your own terms than somebody else’s terms, because I know I’ve had experience in front of the yard, and if I’m taking over the yard, at least I can represent the independent dudes in the right way and make sure everything runs smooth, so I did. I was the first independent guy that ever ran a gang yard.

I kept the yard for four years until I asked for a lateral closer to home to try to get my visits, which sent me out to Lee County in Virginia.

You’re a guy with a big reputation. What‘s to stop somebody trying to make their name by attacking you?

That’s stuff in movies, you see on TV. It doesn’t happen like that in real life in prison.

You’ve got to understand that if somebody was to make a move like that without getting the reputation, no justification, and no approval from the yard, they mess their whole career up. They’re going to be beat if not killed, they’re going to be maimed, stabbed up, and then they can’t go nowhere. And that’s it.

People are not going to do that. You’ve got to understand that a shot caller is a shot caller because the yard and your own people say, “He is the most qualified to lead all of us.” It’s blind obedience with these guys.

I used to have a guy say, “Man, everything that you asked me to do, you’ve done yourself, so I’ve got no problem taking orders from you. Plus, you don’t do drugs, don’t drink so you’re not making inebriated decisions, and you can’t be bought.”

That’s what people like to know, that you can keep control of the yard, make peace for everybody so they could walk around and not feel threatened or they’ll be racial wars or something like that.

In the movies, people go around challenging the top dogs.

That’s the movies. It doesn’t happen like that in real life.

How many people have you killed in prison?

Two. One in 1989 and one in 1990.

The last time I was in any violence was February of 2005 when I was at the old Terre Haute prison in Indiana. There was a guy that became an MMA fighter on the streets. He was in a block with me, he started backing dudes up, beating them up. They didn’t have a chance because he was putting them in a hold and choking them out. He was hurting them pretty bad.

We had to keep guys from his block for like three, four, five weeks at a time, so they didn’t go to work or out on the yard. One time, this dude got in an argument with two of my homeboys from Ohio. He was in his cell and two of them fighting, him and Jay, and he hurt Jay a bit,

When I heard this, I went over to that side of the block and Jay said they got into it, and this and that. The dude comes out and he’s saying something. I said, “Whoa, now you act up and doing all this disrespecting. Now you need to just go back to your cell.” He told me, “Man, fuck you. Who the fuck are you?”

I said, “You’re going to get a chance to see if you keep running your motherfucking mouth.” He’s like, “We can take it in the cell” because he had his brothers around.

I said, “Well, let’s go. You ain’t scared of nothing.”

He said, “I’ll be right back.”

He comes in my cell, and I had a knife on me, he had a knife on him. I didn’t even give him the chance to pull out the knife because I got him first. He hit me in the head a couple of times, and I hit him one time, he went down, and then he couldn’t get up because he was dazed, and he said, “All right, I’m sorry.” I looked at him and I said, “Yes, I know you are, but we still got to go through this.” Then I just popped him in the head.

You get hyped up when you’re doing stuff like that, so I’m thinking, “Oh, man. Now I’m going to go back to the ADX for doing this.” I had already been there twice. I hit this dude so hard with this pipe that it reverberated on my fingers, and it actually made my fingers bleed. I had to wear a rag around the pipe and it was all bloody. I walk out the door to see all these guys on the other side of the range staring. I said, “What the fuck are you guys doing? Get out of here.”

I went to my next door neighbor and he made me a cup of coffee. I’m drinking a cup of coffee as I went in and kicked the dude a few times. He’s still out. He’s got a lot of damage on him. I don’t really know why I did it. It gets out of hand, and they don’t know what they’re getting into. I pick him up, and we’re on the 2nd tier and I toss him off the tier.

Did he survive?

Yes, he did. They took him to the hospital and operated on his brain. They took a third of his brain out because it was all badly damaged, and he has no long-term memory, don’t know who his family is, and stuff like that. He had to learn how to walk all over again.

Did you get punished for that?

Yes, I went back to the ADX. I did five more years at the Federal Supermax, Colorado.

That’s a terrible story for that poor guy.

He wasn’t a poor guy.

You were incarcerated with Timothy McVeigh and the Unabomber. What were they like?

Timothy McVeigh, I didn’t know him. I just saw him. Him and Terry Nichols were on Bomber Row. Listen, I don’t have nothing for them niggas. They’re pieces of shit to me, anybody that blows up buildings with little kids in them. If you know you’re going to kill these kids, I got a problem with that.

I don’t have no love for them and to clarify that, I don’t have no love for the terrorists either, because they’re destroying people at random, people that are just trying to make a living and living life. To answer your question, yes, I’d seen them up on the ranges, but I never talked to them.

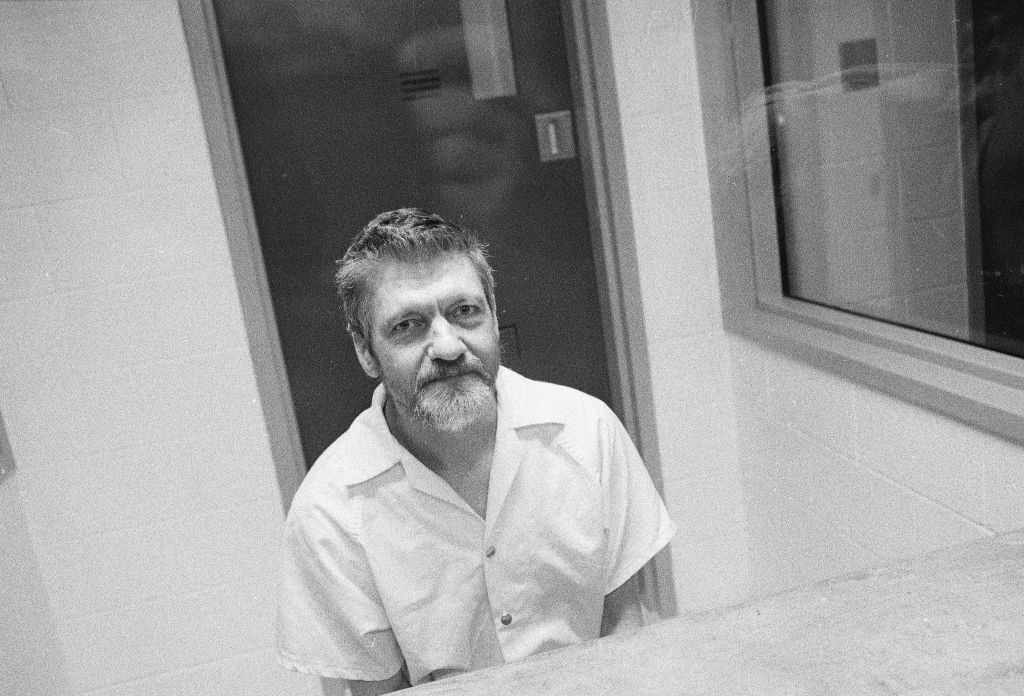

I did talk to Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, five, six, seven times. Maybe a little bit more, I wasn’t counting.

I tell you one thing that impressed me about him. The dude was one of the smartest dudes I’ve ever met, a mathematical genius. We used to say, “Hey, Ted—” Some dude would just take a calculator, one of those handheld, solar calculators, and put 25 numbers together at random, and times five, and that dude would take 30 or 40 seconds and could tell you exactly what the number was.

Dude was an Einstein, as far as mathematical problems. I thought, man, what a waste that you were doing what you were doing out there. I’ve looked at other guys in prison, too, not just Ted, and I’ll say, “Damn, what a waste. You guys could have really made an impact in society had you used that for good instead of the bad things.”

How did the other inmates react to the Al-Qaeda terrorists?

Most of them don’t have no love for them. Now, I wasn’t on the range with them. It’s been so many years now since I was around them, in the same block. They got Mustafa, Kaleef, and the ones that came from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other places around the world.

They brought them here to the United States and some of them went to Guantanamo Bay. Then they were bringing so many into the United States that they actually built a special unit at the Supermax in Colorado, just for those guys. They ended up taking them all out of the blocks that they were in and putting them over there. They weren’t allowed to rec with us or be around us, physically, because if they were, yes, most of them would have had something done to them. Because some of them were straight up haters.

The prison population would have attacked them?

Oh yes, because listen, I’ve been around them, spoke to them, especially the ones they brought over from abroad. They hate everything American. It doesn’t make a difference that they’re in prison or not. It doesn’t make a difference. They didn’t even like the other Muslims because they thought, “You’re American Muslims and we don’t acknowledge that. If you really want to do something, you should have did something to the government.”

They’re straight haters, man. You could hear it in their voices.

They had a special block called H-Block, a unit originally designed to house all the American spies that were convicted, but before the block opened up, they debriefed all of them, so they didn’t put them in there.

So they had all these international terrorists in there. It’s a self-sufficient block. It’s got its own infirmary, its own dining place where they make the food and stuff like that. A lot of them went on hunger strikes.

This is something your readers won’t know about, because they made it a real secret. They had a special room in H-Block that had this big, giant, heavy steel chair bolted into the floor and had leg straps and arm straps, sort of like an electric chair. Once they lost like a third of their body weight or something like that, they would strap them in there, strap their hands back, and they would take a hose, literally, and push it up their nose, down into their stomach, and feed them like that.

Some of them went on for months and months. Then they finally started eating. There was one guy that they always talked about. They had to strap him in there 123 times before he started eating.

You knew Tupac’s stepfather there. Did he have theories about who killed Tupac?

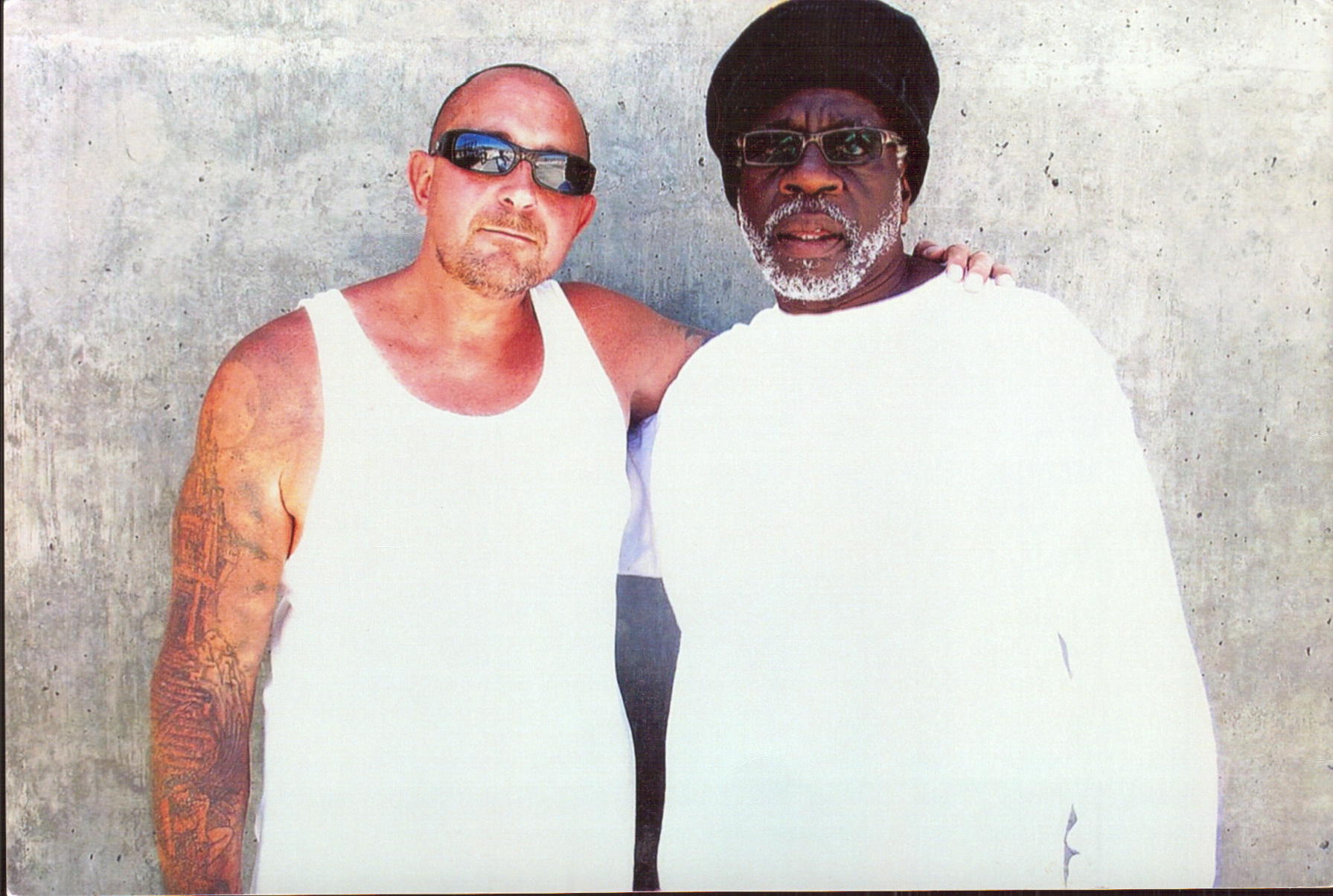

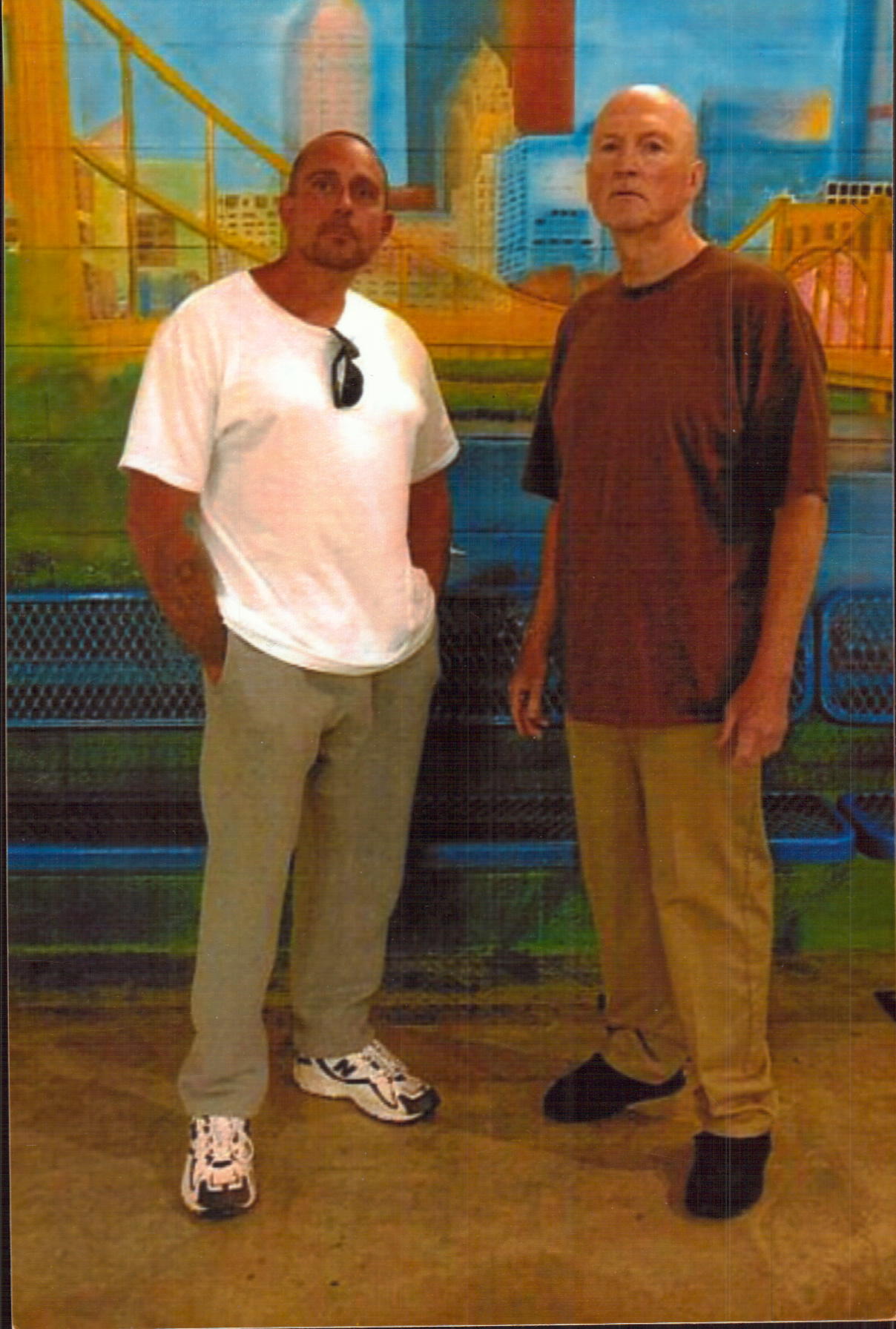

Doc was a great man. I knew him at the ADX and then we spent four years together at Victorville. He was a really good, kind-hearted, polite, respectful man. I liked him unconditionally.

He’d been down, at that time, 32 years or something like that. He used to share all his stories with me about being on the streets. He adopted Tupac as an infant, when he married Tupac’s mother.

Yes, he had some theories, but he kept them to himself. We’d sit out on our front porch, in between our cells, and I’d say, you’ve got to be a little cool? He said, “I believe I know who did it.”

You don’t press for nothing like that. You don’t try to dig. In prison, it’s always better when dudes don’t say nothing. That way, you don’t have a responsibility carrying that information or that burden around with you the rest of your life.

What do you do for fun in prison?

Oh, man… When I was younger, I used to play the basketball and softball. I always loved working out. Then, ’93, they started taking all the weights out, after the Lucasville riot. I used to like to play bocce a lot.

Bocce?

Yes, I love the game. When I was at Victorville, they didn’t have a bocce court. I ended up talking to the warden and getting him to spend the money to build a court.

Are there ever moments in prison where you just have some fun, have a lot of laughs?

Oh, yes. There’s always those times, especially if you know guys for years and years and you’re comfortable around them. Absolutely. It’s not all violence and plots and all stuff like that. You can have some good times and it might be you’re going out on a yard, or you might make a meal and go out whether it’s in the block or the TV room or wherever you’re at. We’re just enjoying a good meal and sitting around and talking about things, funny situations and stuff like that. There’s a lot of cracking up. It’s not all gloom.

What made you want to write your book about prison life?

Well, I thought about writing this book maybe 15, 20 years ago, but then — I was running in the yard and doing the things that I was doing, I didn’t have time to do anything. The two fiction novels that I wrote, those were actually done while I was at the Supermax. The prison book, I felt this was something that people could learn from.

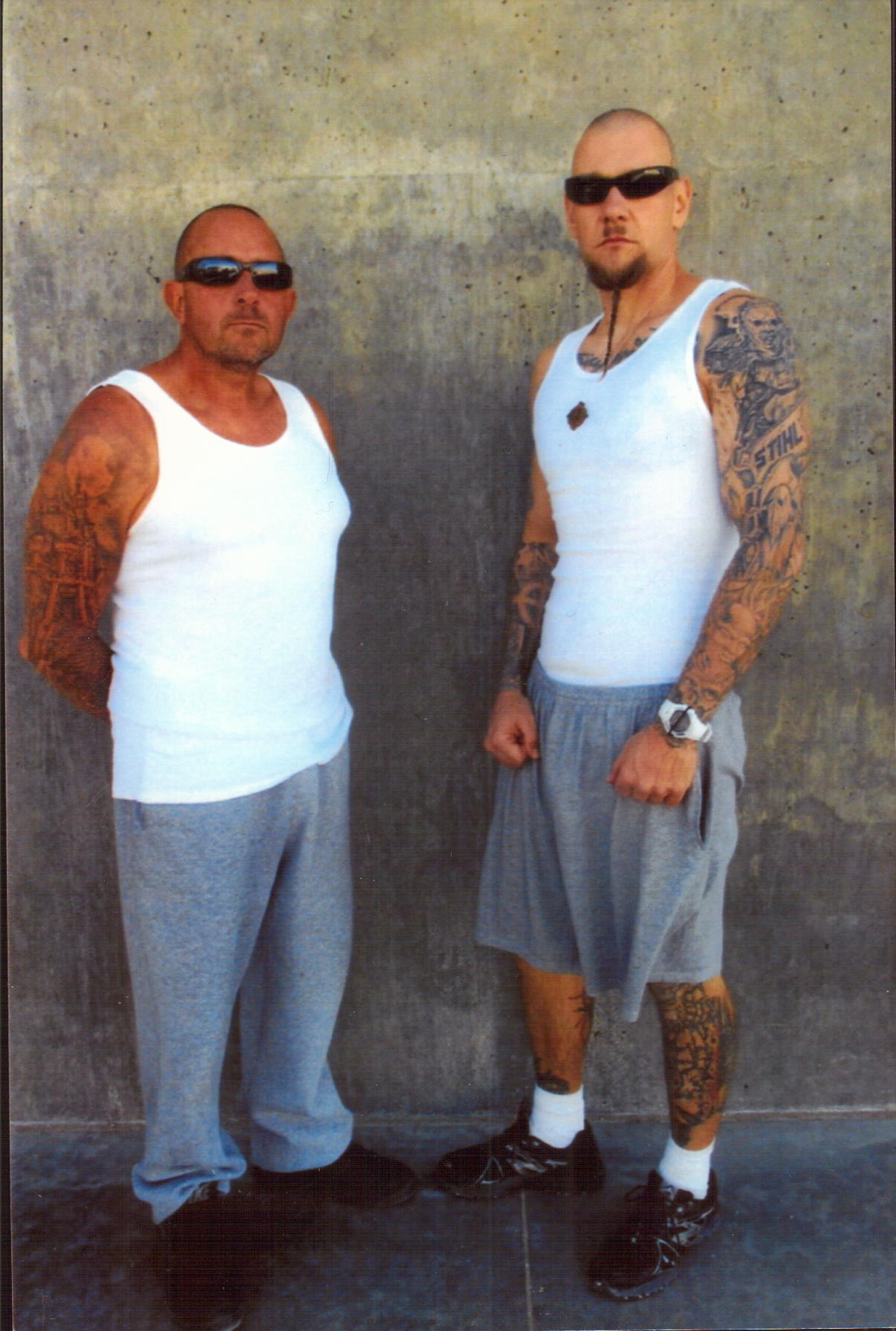

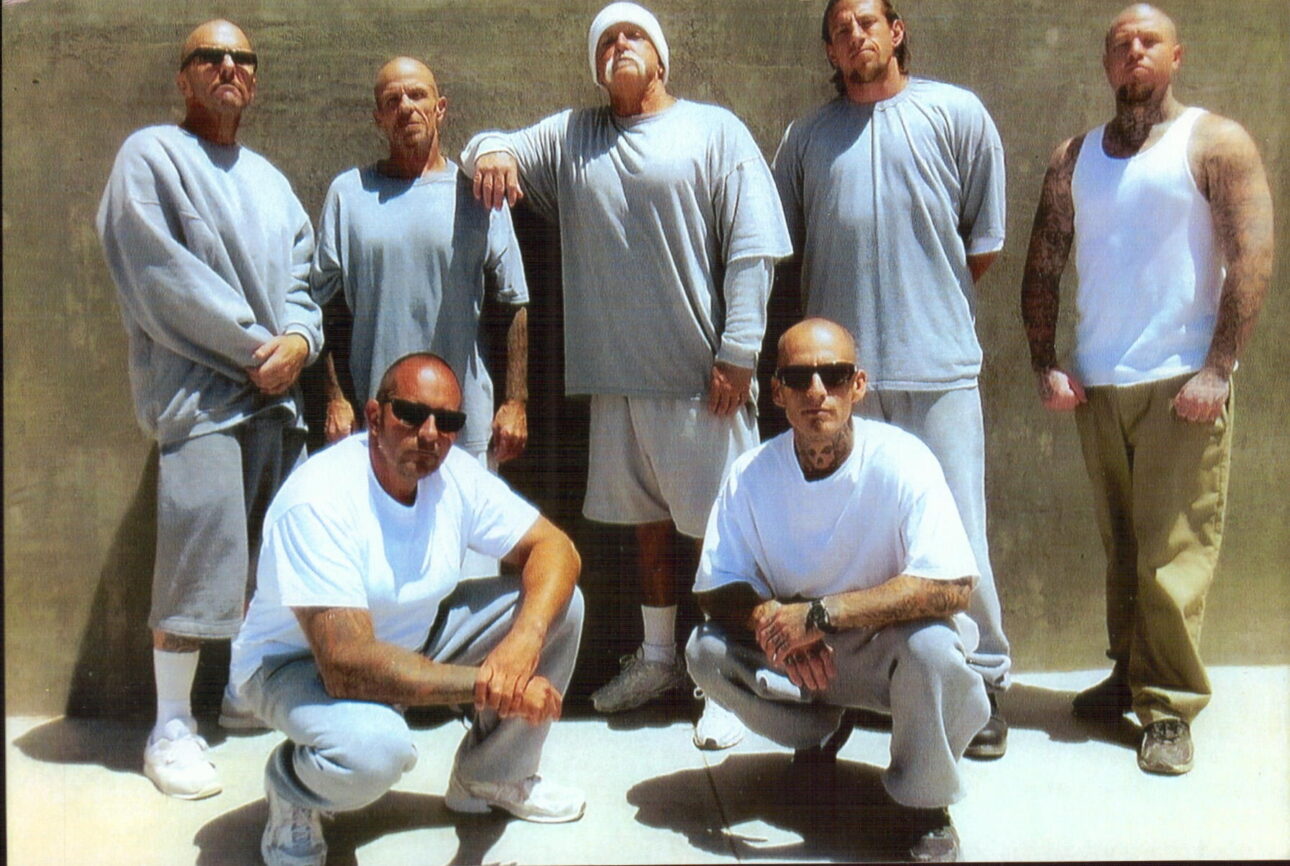

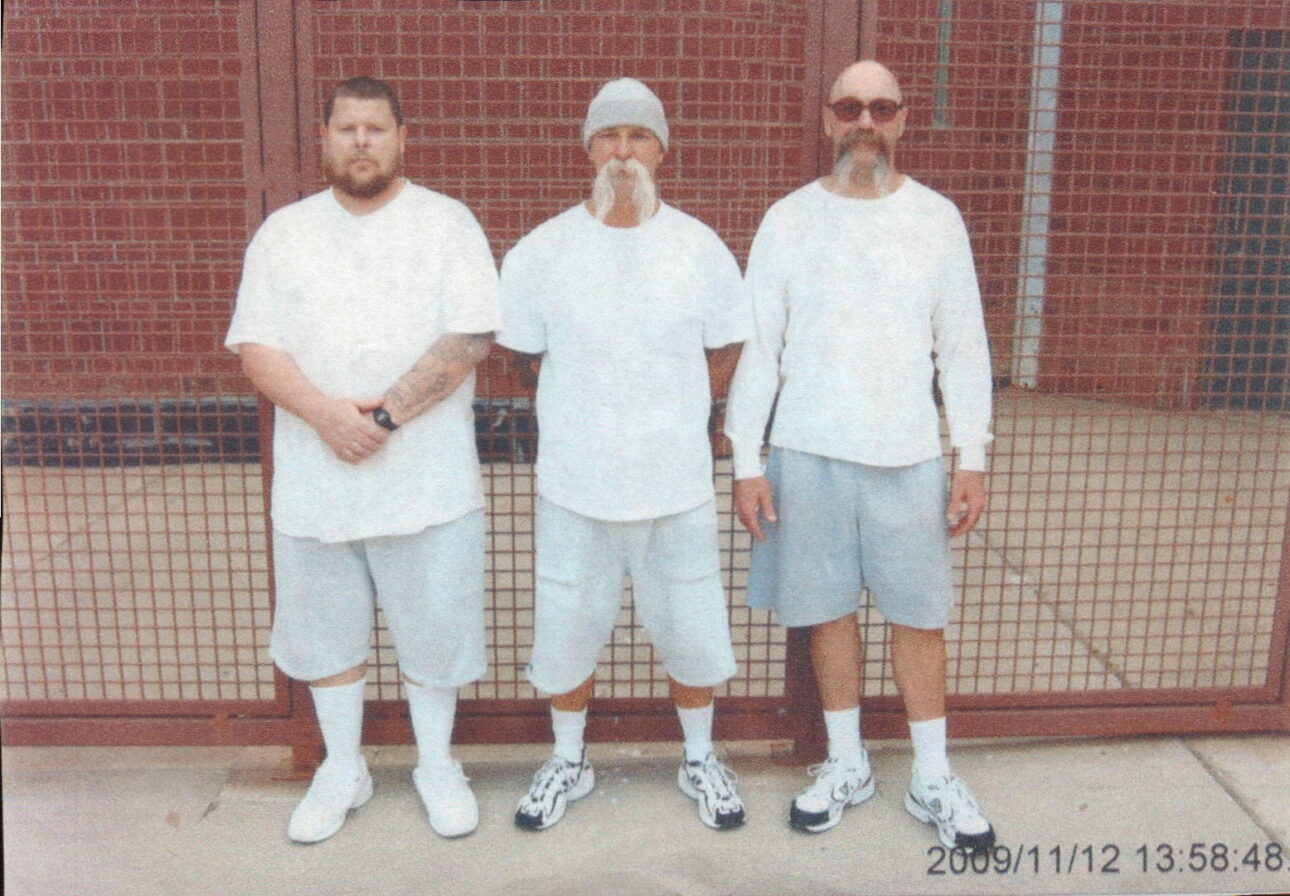

I feel like if anybody’s edging towards crime or prison, this is a book that you can give them. This book is taking time to explain things, and I’ve got like 50 prison photos of high-profile dudes I knew, like Doc, and Kirksey Nix, the founder of the Dixie Mafia, and Woody Harrelson’s father. I got cool with all of those.

At my age now, when I look back in hindsight and see everything that I’ve done with my business, I said, how could people benefit from this, rather than just learn about some violence? What could people take away from it?

One of the things I stress is that you can be into crime, and you can be making a shitload of money out there, but eventually you’re going to get caught. When I was at the ADX, I was with Juan Abrego, who was the biggest drug case in US history. He was the cartel chief for Mexico. Then you got Juan Matta-Ballesteros, who was the Honduran cartel leader for back in the day. He was involved in the Iran-Contra debacle in the ’80s with Ronald Reagan. Juan Matta’s worth is $3.5 billion. That’s with a B.

The money doesn’t help them. They can look out for family and friends but as far as their own self, they’re going to spend the rest of their life in prison, spending a couple hundred dollars a month at the commissary.

What do you think it’ll be like when you get out?

I can’t even count how many times I’ve been asked that. You know what I tell dudes, I say living in prison, you’re always adapting 24/7. You’re adapting to the environment. You’re adapting to people’s personalities and their good moves and bad moves and how the administration is doing things that day. You continuously evaluate what’s going on and adapt. I feel like once you get on the streets, it’s easier.

I don’t think it’s going to be a hard process to adapt to it. I know what needs to be done. I would rather live in a cardboard box on the streets than do any crime again.

I’m 65 years old. I’m too old for it. I just want to be able to get out eventually and live the rest of my life out there in some kind of peace. I’ve always loved writing, so I think I’m going to have a lot of opportunities to write.

Also, I’ll be able to go to universities and talk to students that are in different types of classes, criminal law or law enforcement, and talk to them about what it’s like in prison. So that they have an understanding they can express to whoever they’re talking to.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.